In a week when another Celtic song is under attack from the mainstream media it’s worth remembering that this is nothing new…

Sixty One Years after The Celtic Song is first played at Paradise, Will the real Liam Mallory Stand Up?

Sixty one years ago, on 14 October 1961 Celtic defeated Stirling Albion at Celtic Park by five goals to nil. The goals were scored by Bobby Carroll, a hat-trick from John ‘Yogi’ Hughes and a late strike by John Divers Jnr. A crowd of 22,000 were at Celtic Park to see these goals being scored and they also got to hear for The Celtic Song by Glen Daly played over the tannoy for the first time ever…

And there’s a mystery surrounding The Celtic Song that Jamie Fox can clear up for us today….

Will the real Liam Mallory Stand Up?

“They seek him here, they seek him there

Those Frenchies seek him everywhere

Is he in heaven or is he in hell?

That demned elusive Pimpernel”

On both the Celtic Song and John Thomson Song ‘new lyrics’ are credited to Liam Mallory. However, the words of these Celtic classics didn’t come from the pen of this mysterious and subsequently elusive character.

The lyrics of the John Thomson Song were roughly contemporary with the Celtic goalkeeper’s tragic death at Ibrox, while the Celtic Song had come, via the Donegall Road home of Belfast Celtic, to Glasgow at about the same time as the arrival of the ‘Clown Prince of Parkhead’ Charlie Tully in 1949.

14th October 1961, Glen Daly’s The Celtic Song was played at Celtic Park for the first time before a 5:0 victory over Stirling Albion.https://t.co/uwGBqRYJmN

Excellent rendition of it from 1998. pic.twitter.com/hRFoMFEMBt

— Li’l Ze (@LilZe_7) October 13, 2022

The real identity of Liam Mallory was in fact Clifford P. Stanton, who was the proprietor of a Parkhead record shop and another music business on the Gallowgate opposite Barrowland. Glasgow Jazz Promotions, at 271 Gallowgate, was a typical 50’s/60’s record shop with the emphasis on Jazz and Blues recordings, U.S. imports and sheet music.

Cliff, a Londoner, recording manager, music publisher, promoter and talent scout was one of the shrewdest and most likeable people in the music industry. He represented prominent Folk Artistes such as Hamish Imlach and Josh McCrea, promoted ‘Riverboat Shuffles’ on the Clyde, successful Jazz concerts in St Andrew’s Halls and authored a column in ‘Record Mirror’. He was certainly influential in the industry, even securing the services of music legend Tony Hatch as producer on Buddy Logan’s ‘The Rangers Song’ (1961) another of Clifford’s projects.

Stanton was responsible for giving Glen Daly the opportunity to record the Celtic Song and John Thomson Song which were originally intended for the Beltona label. However, as a result of impressive, record-breaking pre-release orders, both songs were finally issued on the more prestigious PYE Piccadilly label.

The Celtic Song controversy https://t.co/54uK97m8WG pic.twitter.com/Pv47CrUNTU

— Celtic Wiki (@TheCelticWiki) October 14, 2022

Although an experienced Variety Artiste, Glen Daly was very much an ‘innocent abroad’ in the world of recording and music publishing. He didn’t realise, for example, that if no one claimed the rights to lyrics or music that they could be quite legitimately claimed by anyone who wanted to exploit them commercially. Realising the sales potential of both songs, Cliff Stanton claimed the rights and consequently his ‘nom de plume’ Liam Mallory appears on both the discs and sheet music as the lyricist.

Glen Daly, who in fact wrote the second verse in Simpson’s on the Strand on the afternoon before the recording session at PYE’s Marble Arch Studios, was quite content with this arrangement. He was excited at the prospect of a recording career and even more importantly the royalties of one ‘old’ penny for each disc sold and a significant share in the profits from sheet music sales.

Why didn’t Stanton use his own name?

Both songs were published by Clifford Music but perhaps the Londoner had some financial consideration in mind (HMRC?) or did the name Liam suggest an extremely commercial hint of the Emerald Isle? Cliff Stanton had no real interest in football, and would reluctantly declare himself an Arsenal fan, but he saw clearly and earlier than most the commercial and promotional opportunities that the game and the major clubs offered.

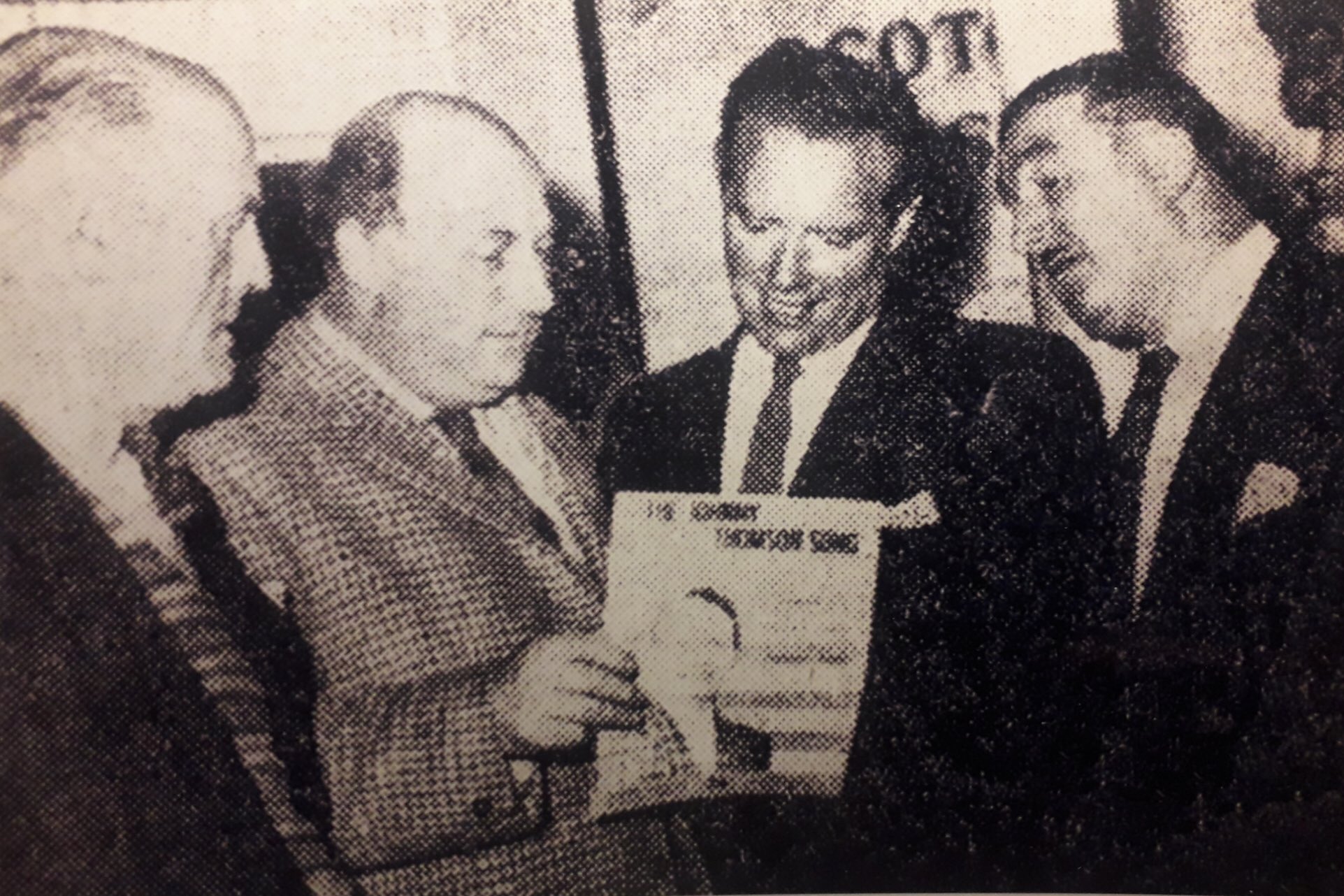

The layout of his Gallowgate shop reflected his retail philosophy. One window devoted to Celtic recordings and one to the other half of the Old Firm. His anonymity would have been guaranteed except for a promotional picture that appeared in the Irish Weekly (1962) where he is featured alongside Glen Daly promoting sheet music and clearly identified as: ‘Liam Mallory of the publishers Clifford Music’.

Cliff’s contribution to Celtic musical tradition continued in 1964 with the release on the Beltona label of the ‘Parkhead March Medley’ performed by the quaintly named ‘Parkhead Enthusiasts’. The tracks included re-recordings of the Celtic Song and John Thomson Song as well as other Irish favourites.

In 1966, on the Pan label, a collection called ‘Celtic Supporters Songs’ included musical content that sounded vaguely and disturbingly familiar. Stanton (AKA Mallory) with his co-writer Hogan McComish claimed to be the composer of some ‘new’ titles: ‘Follow, Follow Celtic’, ‘The Flag My Father Bore’, ‘There’s Not a Team’ and ‘Long Live Celtic’. In an ecumenical gesture, although a committed Marxist from a Jewish background, on the B Side Cliff claimed composition of ‘Hail Glorious St Patrick’, ‘Faith of our Fathers’ as well as a number of traditional Irish patriotic songs.

Morning all, on this day in 1961 the Celtic Song by Glen Daly was first played over the scratchy old PA system at Celtic Park and was instantly popular. 61 years later the song is still sung by fans of Celtic and indeed other clubs, most notably Everton. pic.twitter.com/TYG1e0OR1j

— Lisbon Lion (@tirnaog_09) October 14, 2022

Now where does all this leave the alleged involvement of prominent and much revered Garngad poet Mick McLaughlin who we are often told sold The Celtic Song, based on the overture to the Pirates of Penzance, to Glen Daly for £5?

The overture does of course clearly inspire the traditional and much beloved ‘Hail! Hail!’. However, examination of the sheet music shows that nothing in Glen Daly’s Celtic Song corresponds, or is even vaguely similar, to the Gilbert and Sullivan work. Mick’s cultural contribution to his community was certainly substantial and invaluable but unfortunately The Celtic Song cannot be included credibly in any anthology of his work.

There was however in 1961 a threat of legal action, for infringement of copyright, by the copyright holders of the hit musical ‘The Music Man’ (1957/Wilson) claiming that ‘Seventy-Six Trombones’ had been copied by the Celtic Song. Fortunately, no legal action was forthcoming. Finally, Glen Daly only learned that he was to record The Celtic Song during a break in a White Heather Club tour which allowed him to meet up with Clifford Stanton in Glasgow, where he signed a record contract beginning a long association with PYE Records.

Lord Lucan, Amelia Earhart, Jimmy Hoffa, Glenn Miller. All still a mystery – but at least now the elusive Liam Mallory has been identified.

Some background to The Celtic Song worth recounting…

Celtic Songs – Video: The Celtic Song & Hail Hail The Celts Are Here

Picture the scene: Celtic on the cusp of glory. By hook, crook, bus, plane, train and automobile, thousands of supporters had made it to Lisbon for the final of the 1967 European Cup. The faithful had won the hearts of the Portuguese people with their exemplary conduct and incredible atmosphere before the match. As the Celtic players lined up alongside their Italian opponents in the tunnel, Bertie Auld cleared his throat and began to sing: “Sure it’s a grand old team to play for…”

Each of the Lisbon Lions joined in and Glen Daly’s immortal anthem was soon heard by the supporters. The support sang with the players as the team came into view: “Sure it’s a grand old team to see and if you know the history…” The enjoyment of the occasion by players and fans, in unison, appeared to mesmerise the Inter Milan outfit and gave Celtic the upper hand. That moment is regaled as one of the most iconic in the history of Celtic Football Club.

Throughout the years, supporters have enjoyed singing The Celtic Song at many other great times. It is synonymous with the club. A vocal monument to Celtic. However, it is an often-overlooked fact that fans are actually singing a combination of two different songs on the terraces – Hail Hail The Celts Are Here and The Celtic Song. The latter is played on its own over the speakers at Celtic Park before every home match, as the teams emerge from the tunnel.

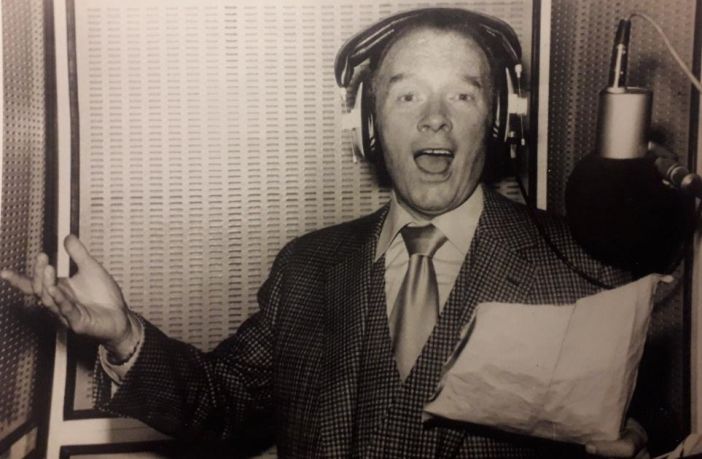

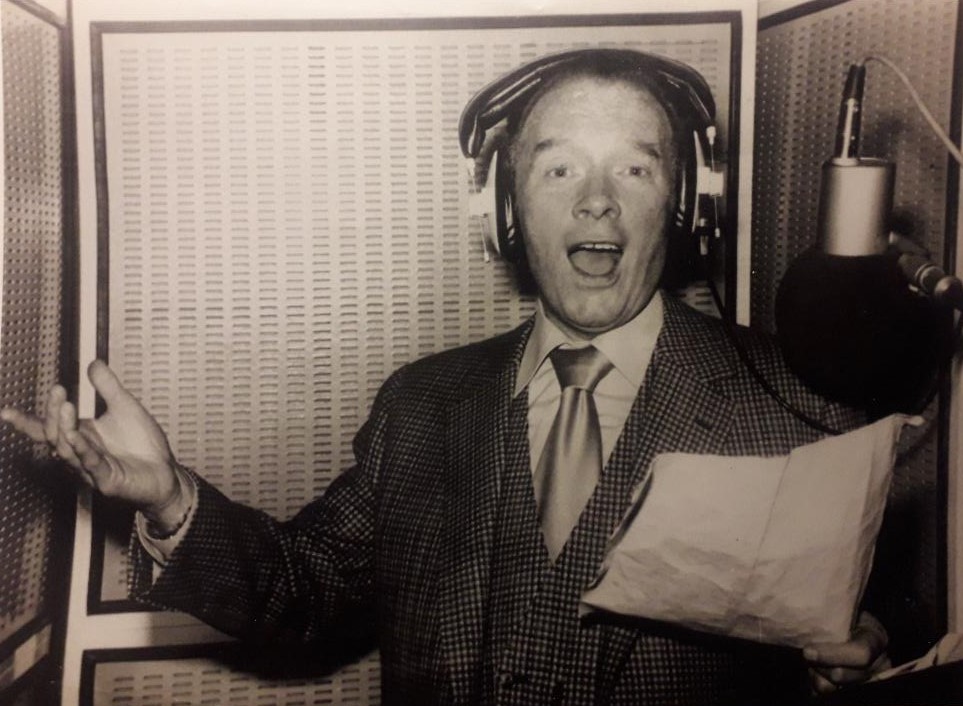

Glen Daly eventually produced the iconic Celtic Song at Pye Record’s Marble Arch Studios in London, in August 1961. On his visit to record the immutable track, he had an hour to kill and reportedly went for a roast dinner in The Strand restaurant, which was among the most reputable in the city and boasted a guest list that was littered with celebrity names. Upon devouring the meal, the Calton born artist is said to have pondered over the second verse of The Celtic Song, which he felt was inadequate.

It was at the restaurant table that a desperate Daly became inspired, when he recalled the voice of Belfast Celtic fanatic, Charlie Tully, who had sung the Antrim club’s classic song at a party in Kenilworth one evening. The lyrics that Glen Daly remembered hearing Tully slur were part of a short ditty that had been a favourite of Belfast Celtic’s support for years: ‘We don’t care if the money’s right or wrong. Darn the hare we care because we only know that there’s going to be a show and the Belfast Celtic will be there.’ The words were a perfect fit. Glen Daly’s anthem was complete, and the song was released on a 45rpm single record in October 1961.

Glen Daly leads the sing song ☘️☘️ pic.twitter.com/ahJtnlRVny

— Willie Collow (@CollowWillie) October 8, 2022

Much like the attachment of This Land Is Your Land to Let The People Sing, Hail Hail The Celts Are Here was connected to The Celtic Song by Hoops supporters in the early 1960s.

Hail Hail The Celts Are Here can be traced back to a 1917 military marching song by D.A. Estron and Theodore Morse, called Hail Hail The Gangs Are Here. It was set to the tune of With Cat-like Tread, Upon Our Prey We Steal, which was a song featured in an 1879 Gilbert & Sullivan opera, named The Pirates of Penzance. The song had been largely plagiarised by Gilbert and Sullivan, who stole the original version, entitled The Anvil Chorus, from Italian opera composer – Giuseppe Verdi. Verdi had written The Anvil Chorus for an 1853 opera: Il Trovatore (The Troubadour), which in turn was based on the play, El Trovador, written by Antonio García Gutiérrez in 1836!

The lyrics to the 1917 adaption, from which the Celtic chant arose, can be heard in the video below:

A swift modification to make the version appropriate for Celtic Football Club was made and the song was then used on the terraces as a preamble to The Celtic Song.

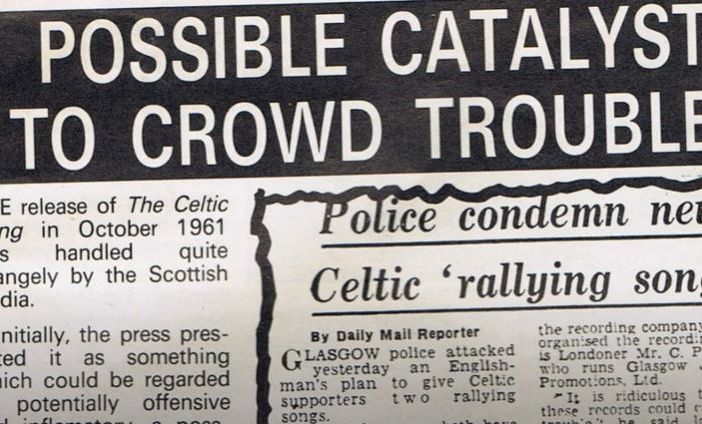

As is aforementioned, The Celtic Song, as a standalone match day anthem, holds a historic and enduring place in Celtic folklore. It was first played over the tannoy at Celtic Park on 14 October 1961, prior to a league match against Stirling Albion. However, following its release, it was immediately under threat from the establishment. The media reported on the song in a very peculiar manner, instantly describing it as ‘inflammatory’, ‘potentially offensive’ and ‘a possible catalyst for old firm trouble’. The Daily Mail even ran a story in October 1961 with the headline: ‘Police Condemn New Celtic Rallying Song’. The piece went on to say:

Glasgow police attacked yesterday, an Englishman’s plan to give Celtic supporters two rallying songs. One of the songs – both have already been recorded – tells of the death of Celtic and Scotland goalkeeper John Thomson, who died 30 years ago. The recording company and who organised the recording session is C.P Stanton who runs Glasgow Jazz Club Promotions Ltd.

“It is ridiculous to suggest these records could cause more trouble,” he said last night.

Common sense eventually prevailed, and The Celtic Song lived on as the soundtrack to the Bhoys becoming champions of Europe six years later. It continues to have an impact, and for that Celtic fans owe a debt of gratitude to the elusive Liam Mallory, and Glen Daly, unless of course they are indeed the same person.

Excellent article. If I may, however make a slight correction. Sir Arthur Sullivan did not plagiarise Verdi’s work. He certainly wrote With Cat-Like Tread as a satire of The Anvil Chorus but the music is quite different and is therefore not stolen. Gilbert and Sullivan had no need to plagiarise anyone’s work. They were great professionals in their own right.