Celtic in the 1930s – And they gave us James McGrory and Jack Connor…

In the first part of this article, I mentioned how the publication of my Copenhagen Diary on the Celtic Star recently had prompted an old friend, Paddy, to get in touch. He wanted to show me a couple of photographs, containing Celtic autographs of the past, which had been in his possession for years. Paddy was looking for some information, background or context for these items.

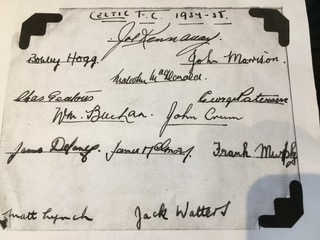

Part one of this story covered the autographed sheet from 1937/38, compiled before the transfer of Willie Buchan and the retiral of Jimmy McGrory pre-Christmas 1937, with the only question remaining as to how it had come about that the Celtic team, or representatives of the club, were in Kingussie in the Scottish Highlands, around that time. I’ll add my own thoughts on that particular query later.

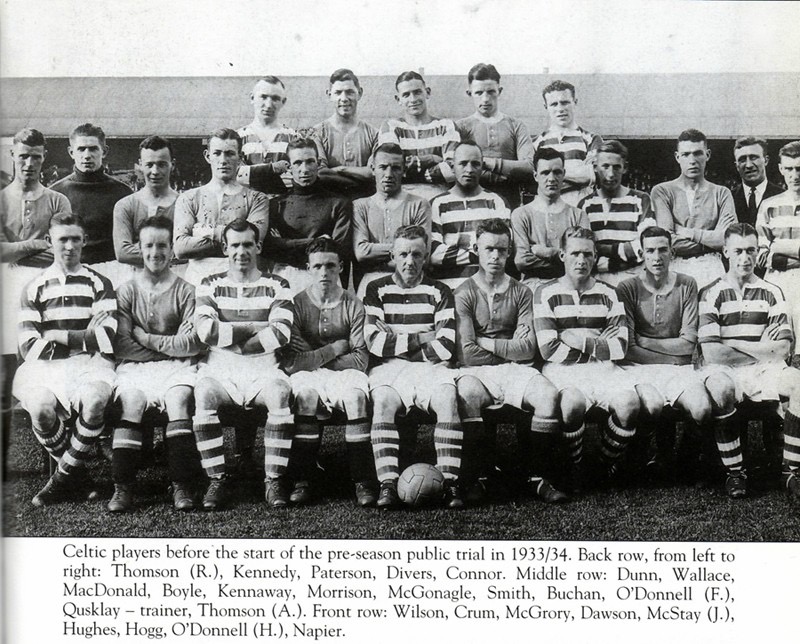

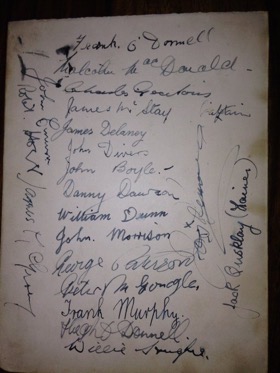

Parts 2-6 of the series (click on ‘Matt Corr’ to find all of these articles – Ed) have discussed the second item, an undated sheet containing the signatures of twenty men, some very famous and others unknown to me, however, all clearly associated with Celtic. This photograph had also been handed to the lady whose family owned the Star Hotel in Kingussie, albeit we then established that this very special piece of Celtic memorabilia related to a team several years before the Scottish, and, dare I say it, Empire champions of 1937/38. From 1933/34, actually. The mystery deepens.

We have now reviewed the careers of nineteen of the twenty names on the second set of autographs, and in the seventh and final part of the series we will look at a Celt who I have taken a special interest in over the past eighteen months or so, since discovering that he was the grandfather of a very good friend of mine, Joe, something he had played down over the many years we have known each other.

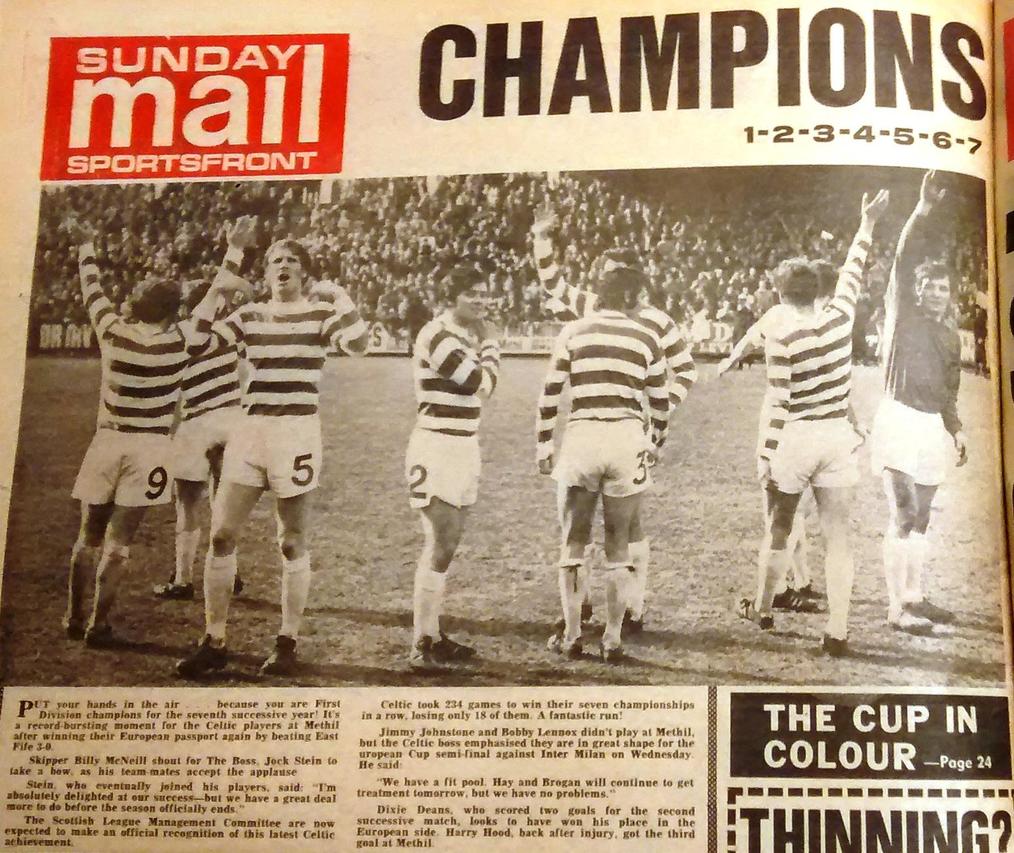

John Connor was born in ‘God’s Garden’, the Irish stronghold of Garngad in the north of Glasgow, on Thursday, 7 September 1911. The Celtic team of the day was in a transitional phase, Maley’s first great side having failed to extend their own world record to seven consecutive Scottish League titles the previous spring. That particular achievement would have to wait until Jock Stein’s Bhoys beat East Fife 3-0 at Bayview Park, more than sixty years later, your 11-year-old author perhaps not appreciating the football history he was watching unfold in Methil that sunny April afternoon in 1972.

Perhaps by way of consolation, the Class of 1911 had won the most prestigious national trophy of the era, the Scottish Cup, following a 2-0 replay victory over Hamilton Academical at Ibrox on Wednesday, 15 April 1911, thanks to goals in the last ten minutes from Jimmy Quinn and Tom McAteer. Both men had grown up in working-class communities, just a few miles apart, McAteer in Smithstone (adjacent to Clyde’s present-day Broadwood Stadium in Cumbernauld) and Quinn in the mining village of Croy, however, their Scottish Cup final pedigrees would somewhat differ.

McAteer’s senior career had started at Bolton Wanderers in 1898, spending four seasons at Burnden Park, three of them in the English First Division, before dropping into the Southern League with West Ham United then Brighton & Hove Albion, where he was appointed captain.

Tom returned to Scotland in May 1904 to join Dundee, where he played for one year before heading back across the border to sign for non-League outfit, Carlisle United. He would spend the 1906/07 campaign on loan at Clyde, the Dalmarnock club having moved across the river a few years earlier from their original home at Barrowfield Park, scene of Celtic’s first-ever trophy win, the Glasgow North-Eastern Cup of May 1889, to a new base at Shawfield Park in Rutherglen.

In February 1908 McAteer made that move permanent, his Clyde side beaten 2-0 by Celtic in a Scottish Cup semi-final replay on Saturday, 27 March 1909, after a goalless draw the previous weekend, both games played at Celtic Park for some reason.

Celts would face Rangers in the final at Hampden in April. Having become the first side to win the League and Cup Double in Scotland in 1907, Maley’s Bhoys followed that up by winning both trophies again the following year. With a fifth successive League title within their grasp, the Scottish Cup was all that stood between the Hoops and a ‘Treble Double’. The more things change… We’ll return to that particular Scottish Cup final of 1909 in due course.

Tom would get his own shot at glory the following season, leading Clyde all the way to the Scottish Cup Final in April 1910, knocking out both of the previous season’s finalists, Celtic and Rangers, en route. The Ibrox side were dismissed by 2-0 at Shawfield, in the second round, before Clyde and Celtic were paired in the last four of the competition for the second consecutive season, this time the ‘Bully Wee’ with home advantage. As if I need any encouragement, that fixture allows me to bring in one of the most colourful characters ever to play for Celtic, albeit if only for one game, Leigh Richmond Roose.

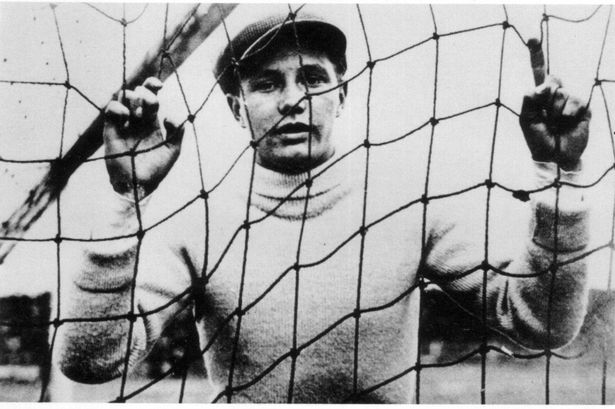

Welshman Leigh Roose was one of the most important goalkeepers in football history. At a time when keepers could handle the ball anywhere within their own half, he had perfected the art of bouncing the ball, whilst evading challenges, as far up the park as the halfway line, before setting up attacks by launching it forward from there. This eventually forced the authorities of the time to amend the rules, limiting such allowable handball to within the goalkeeper’s own penalty area, as it remains today.

Roose retained amateur status throughout his career, although some reports claim that he ‘charged handsomely’ on his expenses. Frequently linked with high-profile ladies of that era and drawing media coverage for his exploits off-the-field, he had enjoyed top-flight spells at Stoke City and Everton and was the Welsh international goalkeeper by the time he signed for Sunderland in 1907.

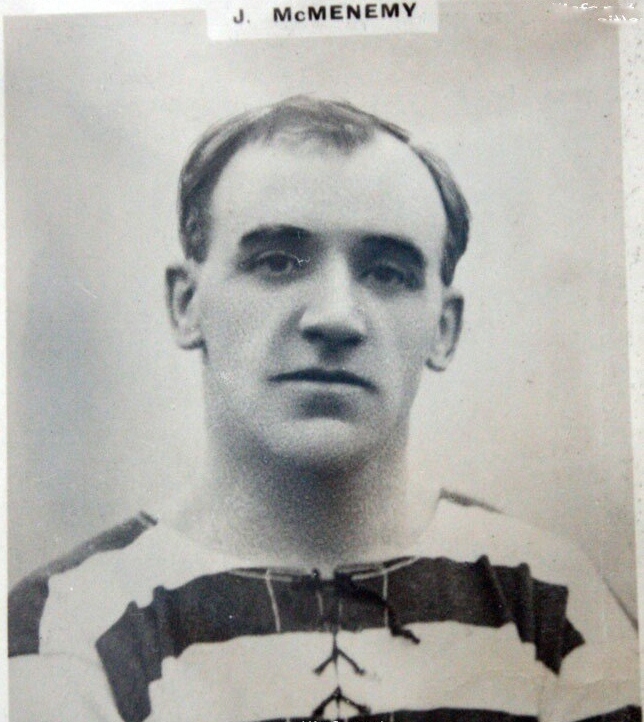

He was still the first-choice keeper on Wearside when he turned out for his country against Scotland at Rugby Park, Kilmarnock, on Saturday, 5 March 1910, in the Home International Championship. The Scottish side that afternoon included five players from Celtic, the dominant force in domestic football of that era, Alec McNair, Willie Loney, captain Jimmy Hay, Jimmy McMenemy and Jimmy Quinn, whilst the great Billy Meredith featured for Wales.

A late goal from Falkirk’s Andy Devine won the match for Scotland, and they would clinch the championship by beating England 2-0 at Hampden the following month, thanks to goals from McMenemy and Quinn. Both Celtic forwards had endured a torrid time at the hands of the Welsh defenders at Kilmarnock, ‘Napoleon’ McMenemy suffering to the extent that he would be unfit for Celtic’s next fixture, the Scottish Cup semi-final against Clyde seven days later.

Whether that factor, or indeed Leigh’s performance that day, would have had some bearing on Celtic’s decision to request the loan of the goalkeeper for the game at Shawfield, will perhaps forever remain a mystery.

In any case, the famous Welshman would turn out for the club in place of regular Parkhead stopper, Davie Adams, who was suffering from pneumonia, Roose, no doubt, wearing his unwashed green-and-black Aberystwyth Town jersey, his lucky charm, under his Celtic kit. Jimmy McMenemy’s inside-forward position against Clyde would be filled by Willie Kivlichan, one of the few players to move directly between Celtic and Rangers, which he had done in 1907, Alec Bennett moving in the opposite direction the following season, despite some suggestions that this was a swap deal. Kivlichan would later pre-date John Fitzsimons, as Celtic’s club doctor, and poignantly would be on duty at Ibrox, his old stamping ground, on Saturday, 5 September 1931, when John Thomson suffered his fatal injury.

Presumably, Leigh would soon require a new prop to alleviate his superstitions, after the semi-final at Shawfield had ended in a 3-1 defeat for Celtic, in front of an incredible crowd of 38,000, Willie Kivlichan scoring for the Hoops. The goalkeeper’s eccentricity was demonstrated when he raced the length of the field to pursue Jackie Chalmers, the scorer of Clyde’s third goal, before offering his hand in congratulations.

One can only begin to imagine the reaction of the visiting support that day, or of the current crop, should Fraser Forster decide to do likewise. Perhaps unsurprisingly after that, this would prove to be his one and only game for Celtic. Roose would finish his English career with spells at Port Vale, Huddersfield Town, Aston Villa and the then Woolwich Arsenal. He joined the army when war broke out in 1914 and was killed in the Somme carnage two years later, in October 1916, aged just 38. Seven months later, on 16 May 1917, Leigh’s Celtic teammate that day in Rutherglen, Peter Johnstone, would also fall in service on the green fields of France, in the battle of Arras. Peter was only 29.

‘To man’s blind indifference to his fellow man.

To a whole generation that were butchered and damned.’

Two young men cut down in their prime, highlighting yet again the horrific and absolute futility of war.

To Be Continued…

Hail Hail

Matt Corr