All football players have the problem of what to do after they have given up the game. In Charlie’s case, this was when he was nearly 33 – the time of life when in any other job, things are beginning to take off. Football had been his life. He had had the opportunity to be an apprentice as an electrical engineer in a firm in London Road, not all that far away from Celtic Park, but had decided against it, preferring to concentrate on his football.

He was unfortunate in that he arrived before the era of the super-rich footballers. His remuneration from Celtic was always adequate, and above the national average, but it would be wrong to say that footballers in the 1960s lived in the lap of luxury. Today on the other hand, players earn an exorbitant amount from the revenues which accrue from TV companies.

It is probably true to say that a player for Dumbarton in 2016 will earn as much proportionately as Charlie Gallagher did in 1972; at Celtic on the other hand, players earnings give every sign of getting out of hand

with a great deal of money being paid out to some players whose ability is questioned. And it is a great deal worse in England and Europe. Some think this is a good thing; others beg to differ.

Where this can be seen to be a bad thing is in the attitude of some English clubs who state quite openly that they would rather be fourth in the English League than win the English Cup. This is blasphemy to anyone with any respect for the traditions and history of the game, but then again fourth in the English League gets you into the Champions League and megabucks! We may shake our heads at all this, but that is the sad reality of the situation.

Yet football was talked about just as much in the 1960s as it is now, and it is an open question as to whether or not it is better. As far as Celtic are concerned, there is no doubt that the 1960s were the two extremes. Things were, frankly, very bad until 1965 when Chairman Robert Kelly swallowed his considerable pride and appointed Jock Stein to the Manager’s job. Things took off almost immediately, and Charlie was proud to have been part of that.

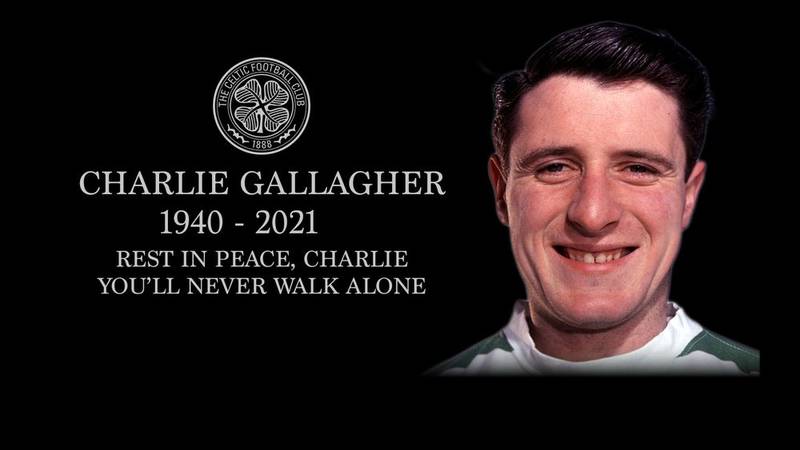

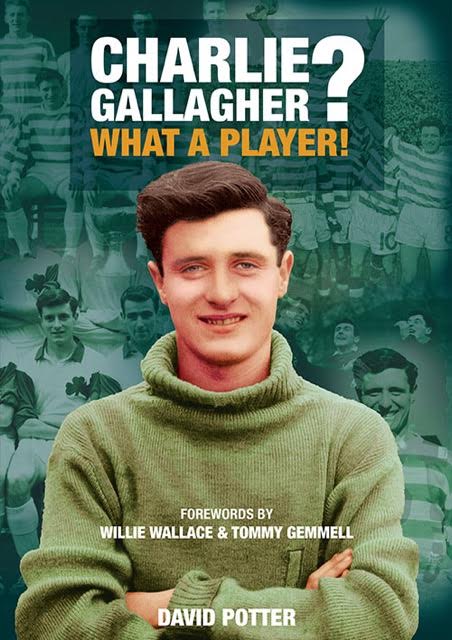

Naturally he was disappointed not to have played at Lisbon in 1967, but he was very much part of the squad, and he had his other compensations as well with his medals in other competitions. All in all he played 171 times for the club and scored 32 goals, won a Scottish League medal in three successive seasons from 1965/66 to 1967/68, a Scottish Cup medal on the day that history changed against Dunfermline in April 1965 and a Scottish League Cup medal in October of that year.

He suffered to a certain extent by being played in different positions. His versatility was not always beneficial to him. In the 1950s when he started to play, positions were fairly rigid, and of course there were no substitutes

until the mid-1960s. (In Scotland, one for an injury from 1966/67 onwards and one for any reason in 1967/68 onwards). This tended to mean that wherever the Manager told you to play, that was it. And when, as at Celtic, the decisions were made by a man who, frankly, knew little about the tactical side of the game, players often had a problem.

Charlie’s deployment on the right wing was by no means a total failure in 1961; yet discerning fans questioned whether he had the pace for that role. When Charlie began, the formation of most teams (not just Celtic) was a

firm and apparently unshakeable 1-2-3-5 with the forwards in a W or an M formation. The wingers and the centre forward were to be supplied by the “fetch and carry” men known as the inside right and the inside left. To a lesser extent, the wing halves did this job as well, but they were further back and had the additional task of keeping the opposing inside forwards quiet. Full backs marked the wingers, and of course centre halves marked the centre forwards.

There was no law that said that all jerseys had to be numbered (Celtic, eccentrically, refused until 1960 – and even then the numbers were put on their pants! They carried out this revolutionary move for the first time in a friendly against Sparta Rotterdam in May 1960 and then it became common practice) but budding young mathematicians

noticed, for example, that in the mid-field a player and his marker always added up to 14! The inside right was 8, he was marked by the left half who was 6, the centre forward was 9 and the centre half 5, and the inside left

was 10 and the right half 4!

For a long time, this system prevailed without anyone objecting. Indeed a feature of the game in the 1950s was the prevalence and indeed the excellence of wingers. England had Stanley Matthews and Tom Finney. Scotland had Willie Waddell, Gordon Smith and Billy Liddell. In domestic football, there was reckoned to be no finer sight that a winger charging down his wing, beating his man, reaching the dead ball line, crossing and in the centre there would be the centre forward waiting patiently to finish it off.

Celtic had had great wingers in the past like Alec Bennett and Jimmy Delaney who was often described as “dashing down the wing like the fire brigade”! More recently, there had been Charlie Tully and Neil Mochan. Charlie Gallagher was simply not of that ilk as a right winger.

But the position of right winger itself was now under threat. Under continental influence, a few teams began to send out formations which did not seem to contain any wingers, either on the right or on the left. There was of course no law against this, but the Press seemed to detect some sort of subversion in the 4-2-4 formation with a flat back four, two midfielders and a flat front four. Hearts and Dundee seemed to deploy this formation, and the annoying thing was that it seemed to bring them some success, even at the expense of a few sneers for playing defensive football!

It all depended, of course, on the quality of the players that one had. Team formations do not win matches; players do. And yet to a certain extent, there does need to be some shape as well. The Celtic teams in the early 1960s took the field with the forward line often looking as if it had been simply thrown together whimsically by Mr Kelly. Little wonder that success was not achieved.

One day in 1963 when Jock Stein and Willie Waddell were still Managers of Dunfermline and Kilmarnock, they went to Italy to study Italian team formation. Jock came back from that trip convinced that the old 2-3-5 system was now dead, and that the much maligned 4-2-4 system (wrongly accused of leading to defensive football by some who should have known better) was the answer, even if in a modified way. He realised that the pivotal characters were the midfield men through whom everything was channelled. When he was with Hibs he used a man called Willie Hamilton (whom he often said was the best player he ever managed) for this purpose.

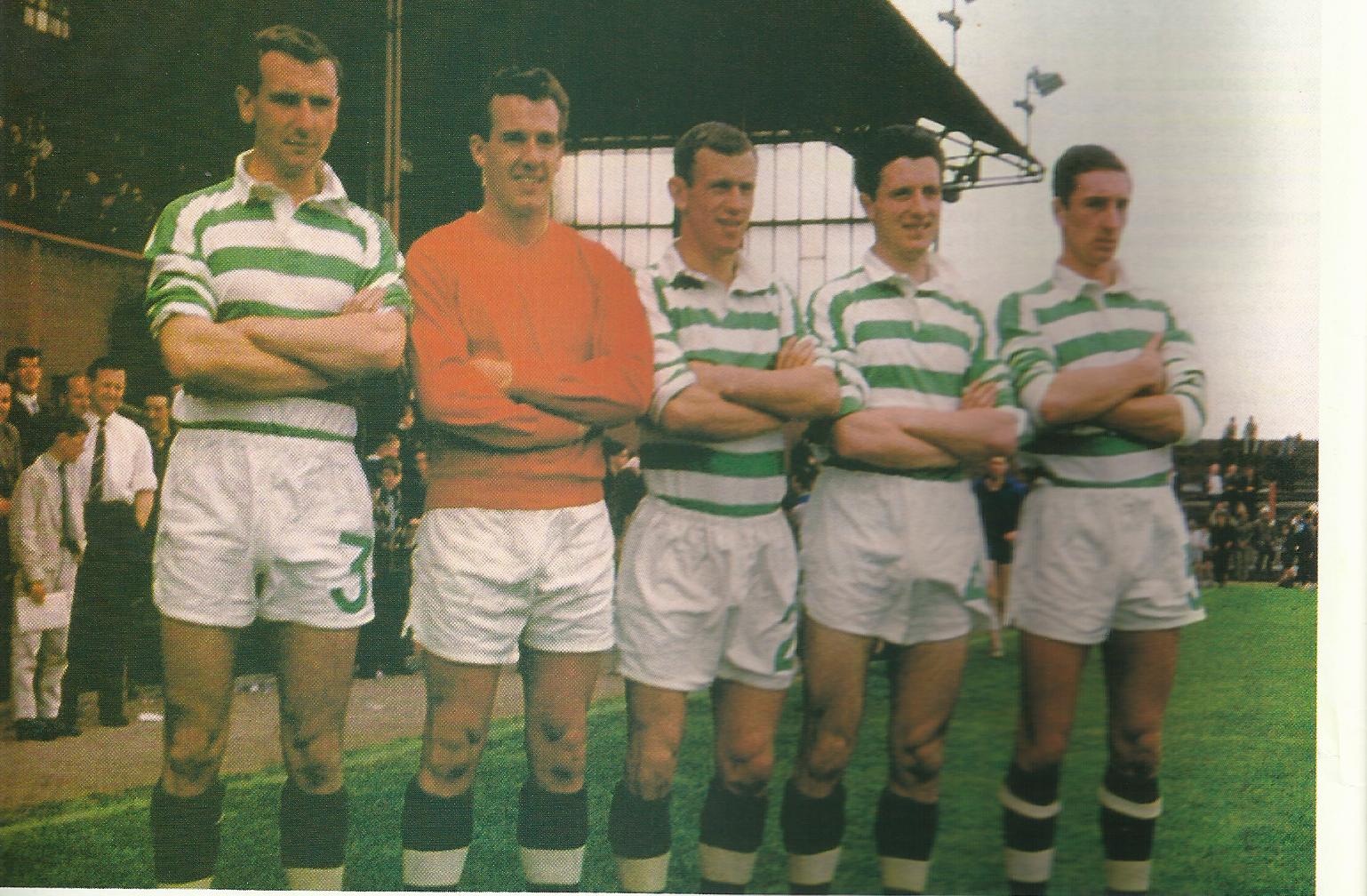

When he came to Celtic, it was to be Bobby Murdoch. So where did Charlie Gallagher fit in to all this? To start with, he was an old fashioned inside forward – that was his position in the 1965 Scottish Cup final – but as the team formation evolved (good team formations evolve gradually over a period of time, they are not created overnight) he was more and more the left sided midfielder who balanced Bobby Murdoch on the right. That was certainly the role he played to devastating effect in the great charge for the League Championship of 1968.

A lot of this was due to the fact that Gallagher covered for Bertie Auld, and that was the role that Bertie had played in Lisbon and in the great season on 1967. It was a shame that Gallagher and Auld were so seldom deployed in the same team – the 1965 Scottish Cup final being an obvious exception – for they were both great players. Stein however did have a point that they were a similar type of player, although markedly different in character. Bertie Auld was more “in your face”, more cocky, altogether more aggressive and more sure of himself. Gallagher was more thoughtful, more accurate in his passing, more apparently laid back. One uses the word “apparently” because he could give the impression of being languid and half-asleep for large stretches of the game, but then suddenly he could unleash an inch-perfect pass, or fire for goal.

As important a skill as any was his sociability and facility for getting on with everyone. The Celtic team of the 1960s, like many great sides, had a few firebrands and hotheads who could all get into trouble with referees. Murdoch, Craig, Gemmell and Auld all had their “moments”. Never Charlie Gallagher.

Yet his good nature and sociability did not mean that he was in any way “soft”. Beneath it all, there burned the same sort of the love of the club and determination to do well that there was in any of the others. An ideal team man, one would have thought. So why did Stein, apparently, not like him?

It was more to do with Jock Stein than it was to do with Charlie Gallagher, and it is important to realise that Gallagher was not the only talented player to be, apparently, on the wrong side of Jock Stein. It is important to

distinguish between Stein and his relationship with fans on the one hand and Stein and his relationship with his players on the other. Stein was famously charming with fans at supporters’ functions, answering all sorts of questions with tact and diplomacy. A hostile question would be dealt with disarmingly, a question put by a nervous, tongue-tied youngster would be listened to patiently and answered with kindness.

The Press were a different matter. He could court them and help them out with stories, knowing that Celtic always needed the Press to be on their side. On the other hand, a columnist who had penned something that he took exception to, could be held up to scorn and ridicule. What no-one could do with Stein was ignore him. More than one journalist had testified to the fact that even when you had your back to the door, you could always tell when Stein had entered the room from the demeanour of everyone else.

With his players, however, there is hardly a man who will give Stein a 100% endorsement of love. Bobby Murdoch was generally regarded as one of his favourites, but he told the story of how, when he was now playing for Middlesbrough, he and Kathleen met Mr and Mrs Stein on holiday in Majorca. Bobby was sipping some beer, and Stein gave him a dressing down! The fact that he was no longer a Celtic player did not really matter!

Steve Chalmers scored a hat-trick against Rangers and was immediately taken down a peg or two when Stein said that he thought John Hughes was the man of the match. Jim Craig, a dentist to whom hands were important, was not allowed to wear gloves; John Hughes had seen fit to query why he had been dropped and was taken to Kilmarnock with the Reserves the following night and publicly humiliated in the dressing room by not being given a game. John Fallon has recently written a book featuring all his many complaints about Jock Stein. And wouldn’t we all like to know what really went on between Stein and Dalglish before the disastrous transfer to Liverpool in 1977?

All this seemed designed to show potential rebels who was Boss, but we are still at a loss to answer the question about Charlie Gallagher. He was the model profession, keeping his head down and playing uncomplainingly wherever he was put, whether in the first XI or in the Reserves. What could he possibly have done to earn Jock Stein’s disapproval? We will never know, but Charlie had the consolation of knowing that he was not alone. And of course, he was the first to admit that without Stein, that talented Celtic team would not have won very much.

Gallagher always retained his popularity with the fans who would cheerfully greet him on the street to tell him how good he had been. After retirement, he did have one job in football and that was working as a scout for Celtic. This he did from 1976 until 1978. It was a job he enjoyed, going all over the country to spot talent. It was a job which by its very nature led to more than a few disappointments, if the man concerned was injured or not playing that day or simply having an off day. He did, however, recommend one particular centre forward. This player was an undeniable Celtic supporter and had great talent, but had a reputation of not being a particularly nice character and had a propensity to get into trouble off the pitch.

Charlie’s recommendation was not acted upon by Johnny Higgins (the Coaching Co-ordinator) or Jock Stein, but this particular player went on to have a sparkling career in both Scotland and England.

His first job after football was in “slot television”. When colour television first appeared in the early 1970s, not everyone could afford one. A way of circumventing this problem was by a television firm selling a colour television set at a cheap price and if the customer wanted to watch a programme, he paid for it by inserting money, on the same principle as an electric meter. This involved someone going round to empty the “meter” from time to time, and Charlie did this job along with his old adversary Bobby Shearer.

He also, when he lived in Dumbarton, had a General Store in that town. It sold groceries and newspapers – something that necessitated getting up early in the morning but it was a job that he enjoyed every much for about 5 years. It was there that his wife Mary, who worked in selling houses, began her hobby as a singer in Gilbert and Sullivan opera. By this time the family of Kieron, Paul and Claire were beginning to grow up, all of them proud of their father.

Mary’s operatic commitment began after being invited to sing at a Celtic function when she sang an old favourite like Danny Boy. Someone suggested that she should join the Dunbartonshire Operatic Society, and she duly did so. Her roles were many and various. She played Elsie in “The Yeoman of the Guard”, Tessa in “The Gondoliers”, the Maid in “The Pirates of Penzance”, Katisha in “The Mikado”, Phyllis in “Iolanthe” and Princess Ida in the opera of that name. She often played opposite a man called John Mulvenna who had impeccable Celtic connections!

Mary became an Estate Agent and they later moved back to Bishopbriggs. Charlie sat his test as a taxi driver, a job he did for many years until the bad winter of December 2010. Occasionally he had the melancholy duty of rescuing one particular ex-team mate, sadly no longer with us, when this fellow had had rather too much to drink. Glasgow taxi drivers are of course a breed apart. Famously sociable and knowledgeable about the city, but usually coming down firmly on one side or other of the football divide with trenchant opinions on Managers and players.

Naturally they are reluctant to advertise which side they are on for fear of antagonising or alienating the

other side or even provoking some unpleasant or even violent reaction, but once engaged in conversation, the guard usually drops!

His job as a taxi driver sometimes curtailed his ability to visit Celtic Park and support the team that he still loved. But he recalled the time when the late Bobby Murdoch phoned and asked him if he wanted to go to Celtic Park with him, for the Directors were keen to use their famous ex-players for Hospitality purposes. It seemed a good idea until Charlie asked how much they were prepared to pay for this service. Jaws dropped, for there had been no plans to pay the players! Charlie, needless to say, was not engaged even after the Directors offered to pay the players some remuneration!

Charlie seldom went back after that until Martin O’Neill managed to ensure free admission for ex-players. He was however a regular attender, sometimes along with his friend John Fallon the goalkeeper, and had his own views of how the game should be played. His advice to any young player would always be to train hard and to become as fit as he possibly could. The bad training regime – or even the lack of anything that might reasonably be called a regime – at Parkhead in the late 1950s and early 1960s haunted him, for frequently Celtic were not as fit as other teams and suffered as a result.

The much improved training after the arrival of Neil Mochan in 1964 showed him how important fitness actually is. Therefore his advice always would be to a young player to get fit and stay fit.

Charlie and Mary had 8 grandchildren. Paul has two boys – Matthew and Aaron, Kieron has triplets – Jack, Lewis and Lindsay, while Claire has three girls, Niamh, Eilidh and Cliona who is now a budding gymnast. At the tome of writing, Charlie was not far from his 76th birthday, he remained the charming, modest chap that he always was. He was proud of his Celtic career and it is hoped that Celtic should be equally proud of him.

David Potter

To be concluded later today…