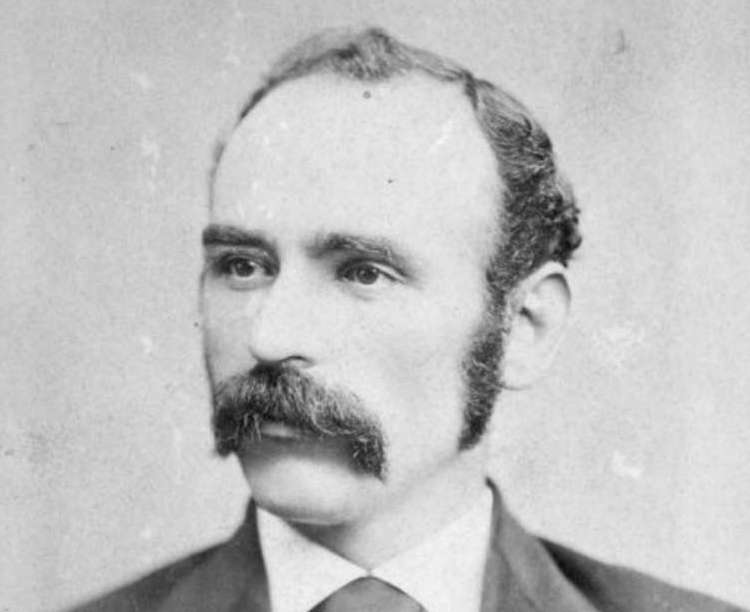

County Mayo-born Michael Davitt was an Irish nationalist, social campaigner and founder of the Irish National League. He was chosen to lay the first sod of grass at Celtic Park and made an honorary patron of the club…

Today, May the 30th, marks the 115th anniversary of the death of Michael Davitt. He was one of Ireland’s greatest patriots and a man with an unquenchable thirst for social justice….

And the plc tell us there is no place for politics in football. Remembering Michael Davitt Organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and co founder of the Irish National Land League and Celtic’s first patron who died on this day in 1906…

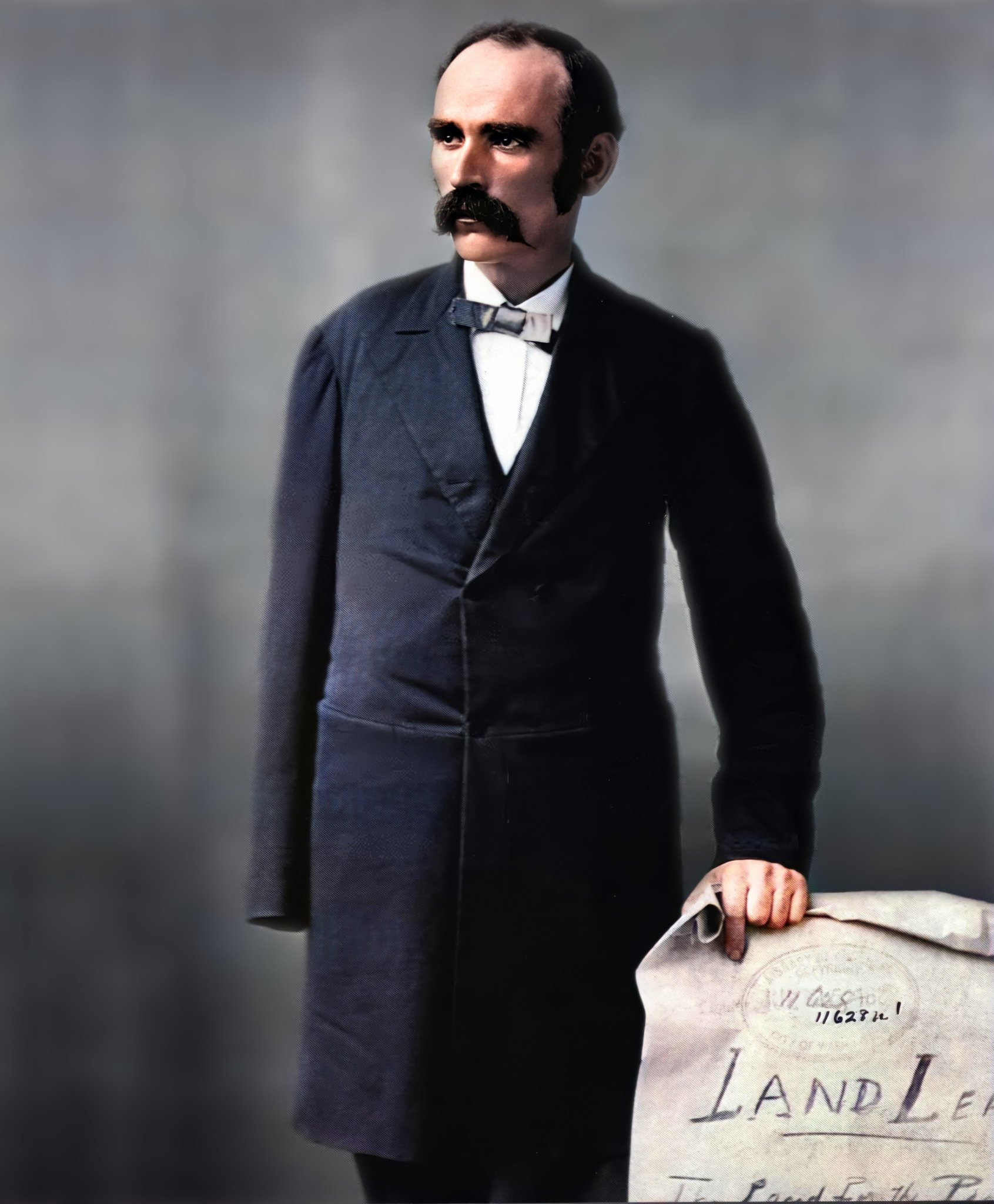

On this day in 1906 Michael Davitt, founder of the Irish National Land League, Fenian arms-smuggler & politician died. Davitt’s drive to organise tenant farmers in Ireland ultimately ended the landlord system with tenants able to purchase their land with government loans…

Irish radical, land agitator, journalist, politician & patron of Celtic FC, Michael Davitt died on this day 1906. Advocate for land nationalisation & integrated education, he exposed Russian pogroms of Jews. His Times obituary said he read “widely if not wisely”….

And the plc tell us there is no place for politics in football

Remembering Michael Davitt Organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and co founder of the Irish National Land League and Celtics first patron who died on this day in 1906 pic.twitter.com/wMWlfXyXMb— Leftwing Badges (@Leftwingbadges) May 30, 2021

#OnThisDay 1906 Michael Davitt, founder of the Irish National Land League, Fenian arms-smuggler & politician died. Davitt’s drive to organise tenant farmers in #Ireland ultimately ended the landlord system with tenants able to purchase their land with government loans.#History pic.twitter.com/mF89e01cZJ

— The Irish at War (@irelandbattles) May 29, 2021

Today, May the 30th, marks the 115th anniversary of the death of Michael Davitt. He was one of Ireland’s greatest patriots and a man with an unquenchable thirst for social justice. #socialjustice #history #Mayo #remembering #Ireland pic.twitter.com/RoAn2HQHa4

— michaeldavittmuseum (@davittmuseum) May 30, 2021

County Mayo-born Michael Davitt was an Irish nationalist, social campaigner and founder of the Irish National League.

He was chosen to lay the first sod of grass at Celtic Park and made an honorary patron of the club.https://t.co/BFd8TOj4WO pic.twitter.com/4AIdPvLIjx

— Celtic Wiki (@TheCelticWiki) May 30, 2021

Irish radical, land agitator, journalist, politician & patron of Celtic FC, Michael Davitt died #OnThisDay 1906. Advocate for land nationalisation & integrated education, he exposed Russian pogroms of Jews. His Times obituary said he read “widely if not wisely”. pic.twitter.com/zV9H9GNdcO

— Barry Sheppard (@barry_shep) May 30, 2021

Remembering today, Michael Davitt. pic.twitter.com/uSzvkGz2Bc

— Paul Larkin*😷 (@paullarkin74) May 30, 2021

Michael Davitt, Irish republican/nationalist, who died on this date 115 years ago (30 May 1906)

A writer, lecturer, journalist, he is known for his Irish Land League activism

Born on 25 March 1846 in Straide, Co. Mayo, to Martin and Catherine (née Kielty) Davitt , small farmers pic.twitter.com/qjC8ukrFP9

— Old Ireland in Colour (@irelandincolour) May 30, 2021

30th May is the anniversary of the death of Michael Davitt.

Read about the great man here 👇 pic.twitter.com/JEtYds1Toz— Davitts GAC (@Davitts1912) May 30, 2021

Remember Michael Davitt, Celtic’s First Patron & Man Who Laid That First Sod Of Shamrock Smothered Turf At Celtic Park

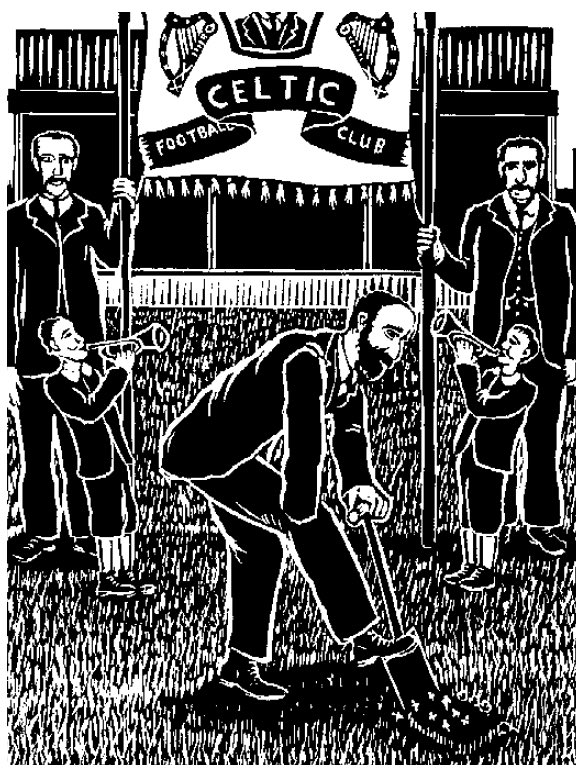

Today marks the 115th anniversary of the death of Michael Davitt. Davitt was Ireland’s greatest patriot and a man with an unquenchable thirst for social justice. In addition, he was Celtic Football Club’s first Patron and the man who was invited to ceremoniously lay the first sod of turf at the new Celtic Park in 1892.

Davitt’s untimely death was due to the extraction of a tooth and the subsequent contraction of Septicemia. In accordance with Davitt’s wishes his remains were taken to Saint Teresa’s Church on Clarendon Street. This was the only Church in Dublin that had been willing to receive the body of his friend and fellow comrade, Charles McCarthy in 1878.

20,000 mourners were to file past Michael’s coffin, which Davitt had left strict instructions that there should be no flag upon. He also stated that black flags should not fly from public buildings.

Michael Davitt & his significance in the Celtic story:

The year of 1892 saw some of the earliest controversial events in Celtic Football Club’s history. For four years previous, Celtic Park had been situated just 500 metres from its current site – at the north-eastern juncture between Springfield Road and London Road. That initial stadium had been constructed in less than six months by Pat Gaffney and a large volunteer workforce. However, the land on which the impressive original Celtic Park stood was that of private property, owned by Alexander Waddell.

The right to continue utilising the 110 yard x 66 yard pitch, complete with a pavilion, a referee’s room, an office, changing facilities and capacity for 1,000 spectators, was costing Celtic Football Club £50 per annum. Despite the club’s charitable endeavour, Alexander Waddell began to take note of the rising Celtic fortune and, rather iniquitously, raised his rental demands by some 800% from £50 to £450 per annum. Such demands were not feasible for a growing club like Celtic and thus the club explored alternative options.

The Celtic committee viewed sites in Springburn and Possilpark before taking advantage of a disused brickyard, adjacent to Janefield Street Cemetery. Productive talks were held with the brickyard landowner, an unlikely saviour, named James Hozier or Lord Newlands as he later became titled. Hozier had been an active Unionist politician, who had worked as Foreign Secretary and Private Secretary for the Prime Minister. He was an enthusiastic establishment figure, who was President of the Lanarkshire Territorial Forces Association and even went on to become the Grand Master Mason of Scotland in 1899 until 1903.

A deal for a ten-year lease had initially been struck, but James Hozier was later persuaded to sell the land to Celtic permanently. A lasting reminder of Hozier’s involvement in the transaction can be found in the shadow of Celtic Park, off London Road, where Mauldslie Street (named after his former home, Mauldslie Castle) exists.

Once the club confirmed their decision to relocate, a large band of volunteers were once more required to construct the new stadium. 100,000 cartloads of earth were used to plug a 40-foot quarry half filled with water. Two tracks were installed, the outer to be used for cycling events and the inner to be used for running. Both were among the best of their kind in the world. A 15-tiered stand spanned the touchline, and a two-storey pavilion was added.

The new Celtic Park was officially opened on Saturday 13th August 1892 with the club’s third, of what would prove to be annual, sports days. Newspaper reports of the time describe the weather that day to be of ‘the most disagreeable kind.’ Indeed, a thunderstorm hovered above the new ground at 3pm. However, the wet conditions were not enough to stop star attraction, Bradley (of Huddersfield), winning the 150 and 100 metre sprint races. Edinburgh distance runners, Hume and Hunter, claimed the top two spots in the mile race; whilst the day saw further distance runs and cycling jousts won by Englishmen.

A quote from the 1932/33 Celtic handbook reflected on the day: ‘The old trouble landlord brought about a change of field, and it was in keeping with it, too, that a seeming impossible site was converted into a splendid enclosure. A case of leaving the graveyard to enter the paradise. A happy title did that pressman strike. The lessons learnt and the experience gained on the old monument to the loyalty and fidelity of the pioneers of the club – did they not give their labour to construct it- were not lost. The splendid pedestrian and cycling tracks, which surround the playing area on which champions the world over showed their paces, added another title: ‘The home of sport.’ It was an auspicious occasion and great day when the late IRB man, Michael Davitt, laid a fresh centre sod of turf from Donegal with a handsome silver spade presented to him by the club.’

As seen in the extract from the handbook, Celtic invited Michael Davitt to perform the penultimate action of the day, when he laid the first sod of shamrock smothered turf, imported from the town of Mullachdubh in Donegal. Michael Davitt was the founder of the Irish National Land League and had served 15 years in a Dartmoor prison for ‘Irish Republican agitation’ and ‘gun running’. He was appointed Celtic Patron at the club’s AGM in 1889 and was a natural choice to perform such a symbolic act in terms of extenuating the Irish identity of the club.

Davitt was accompanied at the new Celtic Park by MP Timothy Daniel Sullivan, who concluded the occasion when he turned to the crowd and sang the unofficial Irish national anthem of the time: God Save Ireland. MP Sullivan had penned the song himself, in tribute to the three Manchester Martyrs, who were executed after a sham trial on November 23rd, 1867.

The grand opening was epitomised by a poetic east end headmaster in the following way:

On alien soil like yourself I am here;

I’ll take root and flourish, of that never fear;

And though I’ll be crossed sore and oft by the foes,

You’ll find me as hardy as Thistle or Rose.

If metal is needed on your own pitch you’ll have it

Let your play honour me and my friend Michael Davitt.

Sadly, the turf was stolen hours after it was ceremoniously laid and the culprit was never found.

Liam Kelly