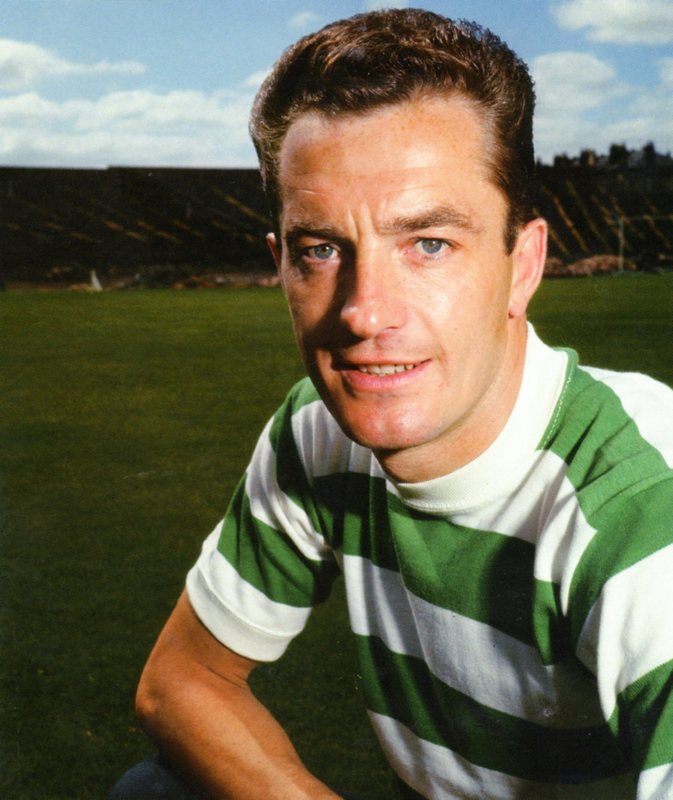

Along with opening itself up to expansion to the vulnerable migrant classes of the 19th Century and providing a home to one of Glasgow’s most beloved Catholic parishes, St Rochs, the Garngad has also given us Jimmy McGrory, the Celtic family’s once in a lifetime talent of superhero proportions, a quick read at John Cairney’s (2007) book, ‘Heroes are Forever: The Life and Times of Celtic’s Jimmy McGrory’ assures us of that.

Another man of Celtic folklore, Stevie Chalmers, was also born in this economically undernourished area just north east of Glasgow city centre. But it is not McGrory or Chalmers this article will focus on but rather the actual area itself, known since the 1940s as Royston but, historically and in respect to its Irish citizenship spanning over two hundred years, I will refer to it by its Gaelic name as many do, as the Garngad.

This area, blighted by financial malnutrition for many a decade much to the detriment of its proud and industrious people, has been so pivotal to the Celtic story so far that it really does deserve more of a mention by those of us who align ourselves with the values of the Celtic family, values such as humility, optimism, collective success, good humour and, above all else, determination.

If we are, as the American sociologist C. Wright Mills suggests, to fully understand our presence as part of a collective unit in the here and now, we must surely acknowledge our beginnings and the process of, what he calls, ‘historical push and shove’. In this respect, I firmly believe that without areas such as the Garngad, Celtic FC and our wider family would be the worse off, and for many reasons.

Garngad’s Irish Heartbeat

Chief among such reasons would be the extent to which Garngad, still with a high number of migrants and people from ethnic minority backgrounds to this present day, was a welcoming home to some of the thousands of migrants and refugee classes who flocked to Glasgow for relative safety after An Gorta Mor (the Great Hunger) in the mid 19th Century. Moreover, in the decades which followed this dark period, Garngad, with, what is now known as Royston Road, running from one end to the other, would play host to a sizeable number of Irish migrants such as the aforementioned McGrory family who came here in the 1870s. The extent to which Irishness is still part of the Garngad DNA is immediately visible to anyone who visits Royston Road, particularly the stretch of road which begins at the St. Rochs Secondary school end which is in close proximity to the Royal Infirmary, sectioned off by the M8 motorway. Along this stretch of road is where An Gorta Mor banners have been displayed in the past and it is also where you will find the Garngad Bar (formerly The Glen) which over the years has been painted in beautiful and bold variations of green, white and gold.

This Irishness of Garngad goes beyond An Gorta Mor migrants however, it actually begins in the early 1800s due in large part to the industriousness associated with the horrifically exploited Irish migrant labourers who were put to work, more akin to wage slavery actually, in what would become the world’s largest chemical works, which was privately owned by the Tennant family of Ayrshire.

Known as the St. Rollox works and having some of its sites based in what is now modern day Pinkston area of Sighthill, it would become the world’s largest chemical works and would corner the market in new chemical processes. However, it operated with great success at an unbelievable cost of humanity and equality as historian Iain R. Mitchell details in his book, ‘Orange, Green and Red; Class, Community and Conflict on Clydeside’, He uses the words of a first-hand witness to the site of St Rollox and its workers taken from 1847:

“They are, necessarily, black and dirty, and as infernal in appearance as we can well imagine any earthly place to be. The heaps of sulphur, lime, coal and refuse; the intense heat of the scores of furnaces in which the processes are going on; the smoke and thick vapours which dim the air of most of the buildings…the acrid fumes of sulphur and the various acids which worry the eyes, and tickle the nose and choke the throat.”

Grotesquely, the vast majority of this army of migrant labour were only being paid a penny per hour, a modern day equivalent would be somewhere in the region of £1.50 – £2.00 per hour in what was, even for pre or early Victorian standards, extremely poor conditions. These, mostly Irish troops of exploited labour, could expect several trips to the Royal Infirmary positioned neatly nearby and could expect to be less trade unionised, if at all, than even the unskilled cleaning staff of similar workforces in parts of northern England. Just like contemporary times, it benefits the riches of a large private corporation if they can rely on the continued exploitation of wages and workers conditions of the exploited migrant classes from which they grab their labour.

The ‘Lazy’ Irish?

It is examples such as these which allows the modern day Scot of Irish descent, particularly those associated with the Celtic family, to be rightfully critical of generations upon generations of anti-Irish, and specifically anti Catholic, racism in relation to a laziness and fecklessness of character. Examples, wholly accepted in public circles, which were to be seen in the widely read pamphlet disseminated in Protestant circles as late as 1923 entitled, ‘The Menace of the Irish Race in Scotland’ – although the text does have a lovely wee section where it clears the Orange Order of any menacing activities, naturally, when it states,

‘…no complaint can be made about the presence of an Orange population in Scotland. They are of the same race as ourselves and of the same Faith, and are readily assimilated to the Scottish race’.

Much of the anti-Irish and anti-Catholic feeling which existed publicly in the west of Scotland, and, many would argue to a certain extent still does to this day, has its roots in a historical misconception that the Irish Catholic is an ‘other’ of lesser stature – a lazy, inward looking, semi-civilised being of alien origin – areas like the Garngad, similar here to the Gorbals and the Calton, are shining examples of just what this supposed ‘other’ can and does achieve despite being faced with widespread public hostility.

Just in case there are any lingering doubts regarding the extent to which anti Catholic sentiment has existed in Scotland, the words of historian Kenneth Lunn from his editorial text, ‘Traditions of Intolerance: Historical Perspectives on Fascism and Race Disocurse in Britain’, ought to be considered here,

‘Anti Irish Catholic sentiment was in fact widely present in Scottish society, it was manifested in national political circles, the Church of Scotland and the literary world…Indeed, in early 20th Century Scotland a number of pressures increased the strength of militant Protestantism and anti-Catholicism.’

The innocent victims of such horrific sentiment are the same people, of migrant heritage, who were easily exploited economically. These same people, many of which were fundamental in constructing the Celtic family from its very origin and subsequently through the generations, were amongst the most industrious and pivotal to Scotland’s contribution to the age of industry, as Bob Doris MSP stated in 2011, ‘…(the Irish immigrants) provided the blood, sweat and toil to help fuel the industrial revolution.’ He continues by stating, rightfully, that the Garngad in particular was pivotal to Glasgow’s international success as a leading industrial powerhouse and ‘workshop of the world,’ ‘…whether it was by digging the Monkland canal basin at Garngad Hill in 1790 or building the St Rochs to Stepps railway line in 1831’

Culture of Inclusion – the Migrant Parallel

Perhaps the most striking connection between the Garngad and that of the Celtic family however is not to be found in its ethnic composition, but rather in its continual culture of inclusiveness, regardless of class, colour or creed. For example, although an area very much with a Gaelic or Celtic heartbeat, the current Garngad is now home to a new migrant. A migrant class made up largely of vulnerable folk from the sub-continent as well as from other ethnic minority populations such as those of the Romani community.

People who, due to the often inhumane nature of our ‘dog eat dog’ dominant white western capitalist culture, are often tarred as ‘others’ or as ‘lesser important’ beings – spot the historical parallels with the earlier Irish migrant. This mindset of ‘othering’ the migrant to almost dehumanised proportions is massaged purposefully and carefully by the state and the tabloid mainstream media, particularly intellect sucking rags such as the Daily Mail or The Sun, in order for those among us who find life an economic struggle from pay packet to pay packet to seek to blame these vulnerable souls, as opposed to venting frustration through collective struggle upwardly to the avenues of power.

In this scenario, areas like Garngad are supposed to be divided and too busy blaming the ‘other’ as opposed to forming a class consciousness and acting in a manner of solidarity and community against the real issues of economic struggle, central to which are only some of the following: a London based bank and media establishment, agendas of privatisation of public services, increasing rents for the private tenant to try and pay, lack of affordable social housing and the public sector workers frozen or capped wage which has happened for the umpteenth time – take your pick.

This new type of migrant, often a chewed up and spat out victim of some of the above mentioned issues within the global context, is fortunate if he or she ends up in the Garngad however, for the culture and character of the Garngad was built by the 19th Century equivalents of these people, supposedly feckless and non-important ‘others’ not of the British culture.

This community looks after such people. An example of this is to be found by way of the local parish priest, a PhD qualified Nigerian, Fr. Thaddeus Umaru. He is the parish priest of St Roch’s who holds regular mass as normal but who has decided to add in a Nigerian mass on a three monthly schedule, he is the parish priest who helps co-ordinate a weekly Foodbank in the community which is open to all, he is the parish priest who helps fundraise for the local schools of the area, Roman Catholic and non denominational alike. He is one of the many inclusive and community inspired souls who is symbolic of the Garngad. After having the pleasure to interview him last year as part of my ongoing research, Fr. Umaru stated just how much the spirit of the community is alive and palpable within the Garngad,

‘The Chapel acts as a centrifugal point of the community…transcending merely the spiritual and religious…it acts as a community and social hub…and I can tell you that there are many local White faces who attend the African dances and are graciously welcomed as we are all of the same parish…we all belong to Garngad.’

So, the next time a comment is made regarding anti-Irish sentiment such as the ‘irish navvy’ or lazy Irish stereotype, tell them about the Garngad and how it was these very people who were amongst the most industrious of the world. The next time a comment is made regarding the anti-migrant and the supposed anti- foreigner stance of the working classes, tell them about the Garngad and its continual community of inclusiveness whether it be in the 19th Century or 21st Century.

Then finally, take the utmost pride in the fact that the Garngad is forever twinned with Celtic Football Club, not just because of McGrory, Chalmers or even the Irish factor, but because like Celtic, our family, it is and always will be, a parish which is open to all.

Sean McDonagh

WRITE FOR THE CELTIC STAR

Do you fancy writing for The Celtic Star on any Celtic related subject of your choice? If so please send your contributions to editor@thecelticstar.co.uk and we’ll get it onto the site for you.

NEW! THE CELTIC STAR PODCAST featuring John Paul Taylor, Celtic SLO…