Yesterday, The Celtic Star reported on the shameful fake news that Sky Sports delivered with farcically inaccurate subtitles accompanying Alfredo Morelos’ interview. The lies and unsubstantiated allegations of racism levelled at the Celtic support, came just a few days after another journalistic blunder within Scottish Football, when it was incorrectly alleged that someone (likely a Celtic fan) had tampered with the brakes on Alfredo Morelos’ Lamborghini, only for the perpetrator to be revealed as a private investigator, who was fitting a tracker to the vehicle.

Turning into silly season in Scotland… Celtic are absolutely right to defend themselves this evening…

— Chris Sutton (@chris_sutton73) February 4, 2020

It would be naïve to suggest that every single Celtic fan upholds the inclusive credentials that embody the club and its support. The infamous Mark Walters incident many years ago demonstrates that and should serve as a warning against any complacency on the matter. However, Celtic Football Club was born representing an immigrant community who faced religious and racial discrimination since their arrival in Glasgow. The Hoops faithful know more than most about how it feels to be on the receiving end of the type of abuse being alleged (without a shred of evidence) and no story shows the inclusive values of the club better than that of the tale of ‘The Indian Juggler’.

In the empire days of old when the British were claiming superiority over India’s population, some Indian Nationalists responded to the colonial jibes that they were not man enough to rule themselves, by proving a point on the football field. Mohammed Salim was one such Indian. He was born in Calcutta in 1904 and began kicking a ball with his peers in an impoverished local village as a teenager. Like many of his countrymen, Salim became part of a football team, who played matches in bare feet against locally stationed British forces. Such matches were a safe and symbolic method of subduing the sense of pre-eminence that Britain had attempted to enforce over the Indian people.

By the mid-1930s, Salim was an integral part of a 5-time Calcutta title winning team, which earned him a spot in the national squad for two friendlies against the Chinese Olympic side. Salim starred in the first match, earning himself many new admirers. Among them, his own cousin, who had travelled from England to witness him play for the first time. Such was the indelible impression that he had made, Salim was persuaded by his cousin to try his hand in Europe, rather than play for India in the second friendly.

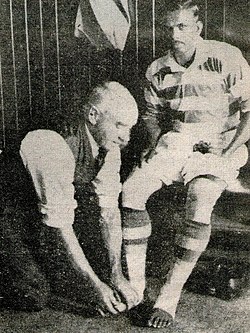

Salim and his cousin landed in England, having sailed from Cairo. No Indian had ever played football in Europe before, let alone Britain. Therefore, the enormity of the challenge to overcome contemporary racist and imperial attitudes should not be understated. Salim’s cousin knew of Celtic’s uniquely inclusive credentials and took Mohammed to Parkhead to meet the club’s Manager, Willie Maley. It is thought that he pleaded with the Celtic boss: “A great player from India has come by ship. Will you please take a trial of his? But there is a slight problem. Salim plays in bare feet.” The Celtic Manager appeared momentarily discombobulated. It was certainly unorthodox for an amateur player to travel from Calcutta with hope of staking a claim in the Scottish professional game, especially whilst professing to play without boots! Nevertheless, after some awkward laughter, Maley granted Salim a trial, in which he would have the opportunity to showcase his talent for the reserve team.

Salim’s first appearance came against Galston on 28 August 1936. He dazzled on the wing and made a trio of assists as Celtic triumphed 7-1 in front of a bumper 7,000 crowd.

The Daily Record broke the story of the trial. Bizarrely headlined, ‘Can he swallow a sword?’, the piece shows the type of mentality that Mohammed Salim was up against:

‘On Friday evening Celtic play Galston in an Alliance game at Parkhead. There is nothing startling about that, but the game is going to draw a bigger crowd, much bigger, because Celtic will play at outside right a dark-skinned young man, Bachchi Khan of the Mohammedan Sporting Club, Calcutta. Mr. Khan has been playing football since he was 14 years of age. He is now 23. Nothing startling about that. He has played for his club against British Army teams. Nothing startling about that. But, luvaduck, the man plays in his bare feet – AND THERE’S SOMETHING STARTLING ABOUT THAT. His cousin is a storekeeper at Elderslie docks and this week he made contact with Willie Maley asking that Bachchi, who is here on holiday be given a run out with Celts. The Celtic manager agreed to give our coloured visitor a place in a trial game, and he took the field sans boots, sans shinguards. And played a delightful game. His crosses to the goalmouth were pictures. The only “protection” he has are elastic bandages – two-and-a-half inches deep – round his ankles, a fact that should make our bandaged toed, heavily booted shin-guarded players think. And if my information is correct Mr. Khan doesn’t give a rap if the pitch is covered with broken glass!’ (Note the reference to Mohammed Salim as ‘Bachchi Khan’. His real full name was Mohammed Abdul Salim Bachi Khan.)

The Glasgow Observer waxed lyrical of him the day after his debut, with the following report:

Ten twinkling toes of Salim, Celtic FC’s player from India, hypnotised the crowd at Parkhead last night in an alliance game with Galston. He balances the ball on his big toe, lets it run down the scale to his little toe, twirls it, hops on one foot around the defender, then flicks the ball to the centre who has only to send it into goal. Three of Celtic’s seven goals last night came from his moves. Was asked to take a penalty he refused. Said he was shy. Salim does not speak English, his brother translates for him. Brother Hasheem thinks Salim is wonderful – so did the crowd last night.

By the time the West Bengal winger had shirked his shyness and scored a penalty to help ease Celtic to a 5-1 victory in his second game against Hamilton Academicals ‘A’, The Scottish Daily Express had him dubbed: ‘The Indian Juggler’.

Salim soon signed for the club, another display of how Celtic broke social barriers in the days of the Empire. Yet, a week after his successful trial period, he became very unsettled. The Calcutta man had been impressive, making early strides towards the first team with his fine crossing, but the media attention he received had been hyperbolic because of his unique story. The Indian was struggling with the public attention and adaption to the cultural changes of Glasgow life.

The club did their best to keep hold of the South Asian starlet, even moving to put on a charity match for the winger with an offer of 5% of the proceeds going his way. However, Salim was desperate to return home and not knowing the significance of the 5%, he suggested that the club donate the money to local orphans, who were to be special guests for the match. The 5% of gate receipts amounted to £1,800 in today’s money, which staggered Mohammed, but true to his word, he donated every penny to the orphaned children.

Mohammed duly departed the club having played just two reserve games, yet his tale resonated with Celtic supporters for years to come. As much as the Celtic support cherished Salim, his feelings were reciprocal, as evidenced by edition number 58 of The Celt fanzine, in which it was referenced that Salim had written to The Evening Times in 1949 to request a copy of Willie Maley’s book: The Story of Celtic.

In 2002, Mohammed Salim’s son, Rashid, revealed that he wrote to Celtic Football Club back in the 1980s to request financial assistance for his father’s medical treatment. In an interview with The Telegraph, Rashid said: “I had no intention of asking for money. It was just a ploy to find out if Mohammed Salim was still alive in their memory. To my amazement, I received a letter from the club. Inside was a bank draft for £100. I was delighted, not because I received the money but because my father still holds a pride of place in Celtic. I have not even cashed the draft and will preserve it till I die.”

This tale began on the dusty crack ridden fields of Calcutta, where football matches were staged against British Army regiments stationed in the city. Salim and his team-mates demonstrated then that regardless of footwear, they were not just equal, but could also better their imperial masters. His move to Celtic was the embodiment of the club’s ethos and a poignant illustration of triumph over tyranny. As the September sun set on his short Celtic career, it is beautifully symmetric that we began to advance towards post-colonial times with the sun also setting on the British empire around the globe. We may be left wondering just what might have been if those brilliant bandaged feet had stayed in Glasgow and forced their way into the Celtic first team. However, the event of his signing for the club is one of the most symbolic and is the epitome of that famous Willie Maley quote: “It is not his creed nor his nationality which counts – it’s the man himself.”

Help raise money for Celtic Youth Development by joining the £1 weekly lottery and you could win up to £25,000 – just click on any one of the photographs below to join. Lots of our readers have already done so and they’re now doing their bit to help fund Celtic Youth Development that can deliver the stars of tomorrow and beyond. And you might even win a few bob too!