In The Times newspaper (not the Evening Times, which has now re-branded as Glasgow Times but the broadsheet ‘London’ Times, there was a recent article that we thought we would share. It’s titled thus:

Kirk asked PM to repatriate ‘feckless’ Irish immigrants

“Newly released documents reveal that a delegation of Kirk representatives demanded that Ramsay MacDonald curb immigration from Ireland and curtail the right to vote for those who were allowed to arrive.

“Representatives of the Church of Scotland and the Free Church raised their concerns with William Adamson, the Labour MP and Scottish secretary, in Edinburgh on May 9, 1930. They demanded he put their demands to the prime minister, which he duly did.

“In a letter to MacDonald, who was born in Lossiemouth, Moray, Adamson said:

“Rev Cockburn, who introduced the delegation, referred to the previous negotiations between the churches and the government’s predecessors in regard to the possibility of regulating the immigration of Irish into Scotland. It is felt the position is now becoming so acute that fresh efforts should be made to stem the flow of undesirable immigrants.

“Figures were quoted to show the large proportion of persons of Irish extraction in receipt of public assistance in Scotland and comprised in the criminal statistics for this country.

“Reference was made to the impossibility of Irish settlers in Scotland assimilating themselves into the political and social fabric of this country.”

The churchmen claimed that sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland could be replicated in Scotland if action was not taken to stem immigration.

The letter said:

“The delegation, therefore, asked the government to take steps to provide effective measures to regulate migration from Ireland, to ensure that immigrants from the Free State who become a public charge in this country be repatriated and to fix a minimum period before an immigrant be allowed to exercise the franchise.”

“The prime minister’s response is not included in the documents, but Adamson attempted to dampen the expectations of the churchmen — stating he could not give any undertaking that their demands would be met.”

So that is the environment that the Celtic supporters who made up the vast majority of the crowd at Hampden lived their lives in a hostile Scotland in the early 1930s. So you’ll appreciate why Celtic’s success in the 1931 Scottish Cup Final would have delighted our grandfathers and great grandfathers and sickened those who reeked of hatred sectarianism and anti-Irish racism. It would be many decades later that the Celtic support gave this a name. SCOTLAND’S SHAME.

David Potter: It is a curious fact that one of Celtic’s best known and most loved Scottish Cup finals was one that ended in a draw! And yet which Celtic supporter, now of advancing years, was not told at first hand by his father, uncle, or grandfather the epic game of 11 April 1931?

It would happen at breakfast tables, tea tables, pauses in the toils of cultivating gardens and certainly on Saturday night and Hogmanay when possibly a little alcohol would fuel the memory and aid recollection of the deeds of derring-do of 1931.

There would be an encomium of Young, Loney and Hay from the early days, then possibly a diversion into Patsy Gallacher with, if circumstances allowed it, a demonstrations of how to do a somersault with a football between one’s knees, and then, inevitably, the story of the ticking Hampden clock of 1931.

The team were 2-0 down, the Mount Florida end was awash with triumphant Motherwell fans holding up their letters of “Give us an M”, Give Us an O… ” and so on until “and what have we got?” “MOTHERWELL!” and then a huge cheer. Sadly, a few blue colours and Union Jacks were seen among them as well, as Motherwell’s first ever Scottish Cup came closer and closer.

Manager John “Sailor” Hunter, so called because of his gait as if he were struggling to keep his balance on board ship, and himself a Scottish Cup winner with Dundee in 1910, was permitting himself a smile as his excellent team, particularly his left wing of Stevenson and Ferrier, were holding the ever determined but now increasingly desperate Celtic attacks.

Even on this most tense of occasions, the six figure crowd had to permit themselves a smile when referee Peter Craigmyle of Aberdeen, ever the showman, refused Celtic a penalty (he was probably correct in his decision) and when Peter Scarff and Bertie Thomson advanced on him to discuss the matter, he ran round the back of the net and out the other side of the goal! It was funny, but there was little else to smile about for the Celtic fans at the packed Polmadie or King’s Park end of the ground.

The terracing was silent and introverted, the banners pathetically drooping, the fans strangely silent. The two Motherwell goals had been fortunate ones, deflections in both cases past the luckless John Thomson, but that was of little comfort now. John was a lonely and in someways forlorn figure in the distant Mount Florida goal, as Celtic redoubled their efforts.

In the stand, Willie Maley could do little other than pray that somehow or other his “foragers”, the “fetch and carry men”, Peter Wilson and Alec Thomson might manage to get the ball to Jimmy McGrory. One could never rule anything out with McGrory around, but the ball was not getting to him, so well policed was he by centre half Alan Craig.

Jimmy Quinn and Jimmy McMenemy, heroes of many a Hampden Cup final in bygone days, sat in numb despair, McMenemy at least with the consolation that his son John, who was playing for Motherwell, would win another Cup winner’s medal and bring the family tally to the scarcely believable nine – Jimmy in 1904, 1907, 1908, 1911, 1912, 1914 and 1921 (with Partick Thistle) and John in 1927, when he was a young player with Celtic and called in at virtually the last minute to play alongside Tommy McInally.

But the general air in the Celtic camp was one of gloom, particularly those who could see the Hampden clock with the minute hand now more or less pointing straight down to half past four to indicate that only ten minutes were left. “Well, well, well, the clock’s ticking well!” said someone who clearly wanted it to speed up and the game to finish.

Were there claret and amber ribbons for the Scottish Cup? How would it look?

The weaker brethren among the green and white brigade were now beginning to head up the steps of the terracing, pausing now and again to look back wistfully on the sad scene unfolding beneath them. There was the odd curse, but the main mood was one of resigned acceptance of what seemed now inevitable.

The team had played well that season. They had won the Glasgow Cup and had made their best League challenge for a few years but had lost to Partick Thistle on a barely playable pitch, and had then drawn with Dundee and Hearts, and it now looked as if Rangers were going to win the League again. And the Scottish Cup, in 1931 the more important of the two trophies, looked as if it were going to Fir Park, Motherwell for the first time.

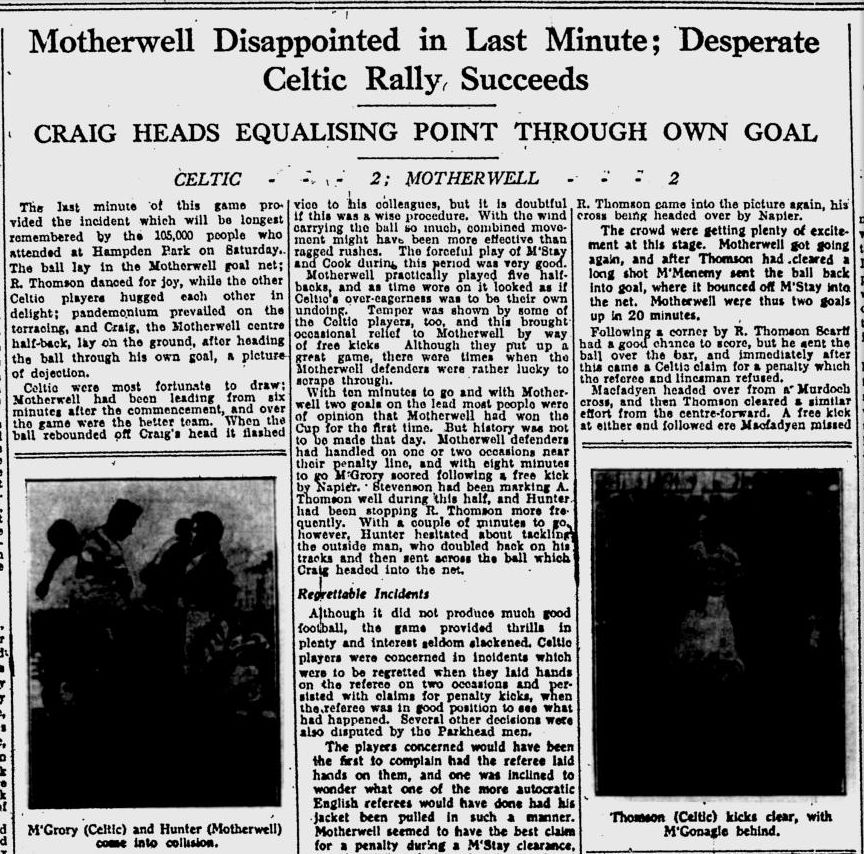

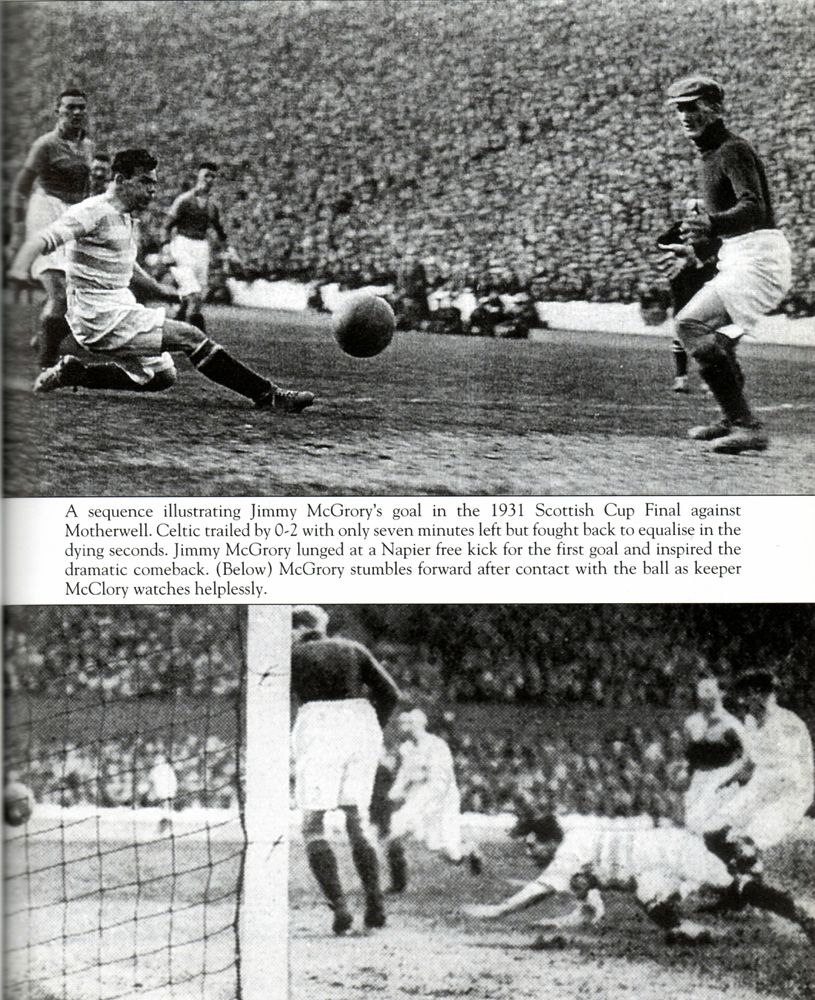

But then a ray of hope. A Charlie Napier free kick looped over the heads of the Motherwell defence and a McGrory toe-poke reduced the leeway, as Motherwell appealed unconvincingly for offside.

There was now more animation about the Celtic players and support, but the general feeling was that it was too late. McGrory was seen to charge back to the centre line pointing to the clock where the minute hand was now beginning its ascent and was indicating that eight minutes remained. The exodus from the terracing now stopped at least temporarily… but the odds were still against Celtic.

The minutes ticked away, and Celtic failed to find McGrory. The newspaper reporters were beginning to think about headlines “Well, it’s Well!” or “Celts Well licked by Mother” and one Motherwell newspaper reporter jumped the gun and sent his report in just before the final whistle!

Celtic Directors beamed their reluctant congratulations to their Motherwell equivalents, as Maley shrugged his shoulders and looked at McMenemy and Quinn with the “we did our best” look.

He steeled himself to shake the hand of his friendly rival ” the Sailor” as Mr Craigmyle ostentatiously looked at his watch and the Hampden clock now clearly saying full time.

But Bertie Thomson had the ball on the right.

Maybe he wanted to have it in his possession so that he could keep it, and then sell it to a friend, but the stentorian cry of captain Jimmy McStay was heard “Get it ower, man!” Ah well, thought Bertie, you never know. It might just find McGrory. It didn’t and centre half Alan Craig rose confidently to head clear. But maybe the ball held up a little in the capricious Hampden swirl, maybe Craig made his first and only misjudgement of the day but the ball hit the side of his head and diverted past his goalkeeper into the back of the net.

When momentous historical events happen, the historian often says that “there was a split second before anyone comprehended what had taken place”. I was reliably informed that it was about one whole second before the Celtic part of the ground erupted, and a lot longer than that before those on the Mount Florida terracing were able to take in the painful event that they had just seen.

I believe it is called “in denial”.

A clear picture remained in the head of one veteran supporter some 60 years after the event of Celtic players dancing with each other, Motherwell players prostrate on the ground in agony and the luckless Alan Craig being helped to his feet, not by his own team mates but by Jimmy McGrory and referee Peter Craigmyle as he beat the ground repeatedly with his fist in anguish.

It was one of sport’s cruellest ever moments.The same veteran supporter saw Motherwell beat Dundee United in the Scottish Cup final of 1991, and was happy for the Steel men. “1931 must have ta’en a loat of gettin ower, ye ken!”

But for Celtic, it was a case of “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Regained”. The Scottish Cup was duly won for the 13th time on the Wednesday night, and what happened in the replay is detailed below.

David Potter

CELTIC: J. Thomson; Cook and McGonagle; Wilson, McStay, and Geatons; R. Thomson, A. Thomson, McGrory, Scarff, and Napier.

Scorers: McGrory, Craig O.G.MOTHERWELL: McClory; Johnman and Hunter; Wales, Craig, and Telfer; Murdoch, McMenemy, McFadyen, Stevenson, and Ferrier.

Scorers: Stevenson, McMenemy.Referee: P. Craigmyle (Aberdeen). Attendance: 104,803

‘Ramsay MacDonald and John Thomson, as they shook hands with each other that day, did not know what was coming,’ David Potter on 1931 Scottish Cup Final Replay

It is often assumed, after the breathtaking and scarcely believable comeback by Celtic in Saturday’s 1931 Scottish Cup final against Motherwell, that the replay was some sort of a cakewalk in comparison with Celtic winning comfortably 4-2. Not so!

Celtic did win their 13th Scottish Cup, and it was generally agreed that they played far better than they did on Saturday, but Motherwell, a great side who would deservedly win the Scottish League in 1932, fought hard all the way earning the sympathy of most people after what had happened to them on Saturday.

The replay kicked off at 5.00pm on Wednesday April 15 at Hampden. The crowd did not quite make the 100,000 this time, but it was still huge for a Wednesday night and contained quite a few men arriving in overalls, working clothes and carrying piece bags.

The 5.00pm start ensured also that schoolboys could attend, and the town of Motherwell saw many shops close at 3.00pm that afternoon to allow workers to get to the replay. 98,579 was a creditable attendance. Once again we curse those who were too late in inventing television, videos, DVDs etc. for we cannot really enjoy this game, other than in newspaper reports!

Celtic started with the wind, and took advantage of a panicky Motherwell defence to lead 3-1 at half-time. Bertie Thomson (in some ways the hero of Saturday) scored twice and the inevitable McGrory the other, although in all three cases the wind played a part in upsetting Motherwell’s defence, still clearly unnerved by their trauma on Saturday. John Murdoch had scored for Motherwell.

The second half needed some grim defending by Celtic, but this was Peter Wilson’s finest hour. Playing against the wind,he had the sense to keep the ball on the ground and of course Peter’s elegant passing was a sight to behold. He “didn’t just pass the ball, he caressed it and stroked it”, as the newspapers said, and he was also a hard tackler in the “Sunny Jim” mould of 20 years before.

George Stevenson of Motherwell pulled one back halfway through the second half, but even then Celtic remained in command with Cook and McGonagle firm in their full back positions, and Jimmy McStay radiating control from the centre of the park.

Three minutes from time McGrory killed Motherwell’s fast vanishing hopes with his second and Celtic’s fourth goal, and much was the rejoicing among the Celtic fans and in Glasgow that night with the rare sight of men with dirty faces and in dungarees and overalls joining in the general merriment and dancing. Although there was no radio commentary, the early kick off meant that the BBC was able to give the country the scoreline, and even a few evening newspapers produced a special very late edition, so that the joy was replicated throughout the land.

1931 saw at least four other famous Celtic events. The tour of America and the John Thomson tragedy are well documented, but there was also a creditable performance in the Scottish League where only a defeat to Partick Thistle on an unplayable pitch and then three late draws to Dundee (twice) and Hearts prevented Celtic from winning the Championship.

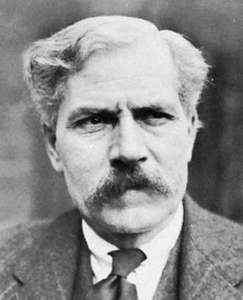

And then we come to the Scotland v England match at Hampden on March 28.The 2-0 victory was good enough (goals from Stevenson of Motherwell and McGrory of Celtic) but imagine the thrill it must have been for Jimmy McGrory and John Thomson to be presented to, not any member of the aloof and distant Royal Family, but to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister!

He was now ageing and now possibly aware that there was no real solution to unemployment in a capitalist economy, yet his kindly eyes and firm handshake showed just why he had come to be looked upon as some sort of messiah in the 1920s.

He was possibly as much in awe of McGrory and Thomson as they were of him, for the Lossiemouth man was a great football fan and a great Scotsman. What a pity he made the wrong decision in August of that year! He had been right in 1914 when he was young and dynamic, but he was now past his best.

You wouldn’t say that about Celtic in spring 1931 however, for a bright future seemed to beckon. September 5 however changed all that. Just as well that Ramsay MacDonald and John Thomson, as they shook hands with each other that day, did not know what was coming!

CELTIC: J. Thomson; Cook and McGonagle; Wilson, McStay, and Geatons; R. Thomson, A. Thomson, McGrory, Scarff, and Napier.

Scorers: R. Thomson, (2); McGrory, (2).MOTHERWELL: McClory; Johnman and Hunter; Wales, Craig, and Telfer; Murdoch, McMenemy, McFadyen, Stevenson, and Ferrier.

Scorers: Murdoch, Stevenson.Referee: P. Craigmyle (Aberdeen).

Attendance: 98,579

David Potter